In this year, the 100th anniversary of the 19th amendment that gave women in the U.S. the right to vote, I’m thinking about American women from that era and the gardens they created.

Marian Coffin (1876-1957) was one of the most sought-after of these women, particularly in the years before World War II. Trained at MIT between 1901 and 1904, one of only four women in the landscape architecture program, she went on to design over 50 significant estate gardens, mostly for wealthy clients on the East Coast.

Her most important commission was at Winterthur, the Delaware estate of her childhood friend, Henry Francis DuPont, and her work there stretched from the late 1920s to the mid 1950s. While DuPont leaned towards a naturalistic approach, Coffin favoured the classical values of balance, order, proportion and harmony based on the French Beaux Arts tradition as taught by Guy Lowell, the director of the landscape design program at MIT. The reflecting pool at Winterthur illustrates these principles. Photographed in spring, when azaleas were in full bloom, it also illustrates how she balanced formalism with naturalism, her preferred approach with the desires of her client, by including exuberant woodland plantings.

The Glade at Winterthur is equally successful at this balancing act. In spring, its billowy, informally clipped shrubs are an explosion of colour, an example of the strong colour contrasts that were one of Coffin’s design trademarks, while in summer, the naturalistic pools and waterfalls provide a shady refuge.

Unfortunately I have no photograph that shows the grand staircase she designed to lead down the hilly slope from the DuPont’s house to the pond, which originally was used as a swimming pool. Midway down the steep stairs, a rounded terrace with a sundial provides a focal point viewed from both the house and the pool. This circular terrace is one of Coffin’s signature geometric elements, as is the circular Sundial Garden, the area she designed at Winterthur shortly before her death.

Photo courtesy of Barbara Israel Garden Antiques.

Coffin often designed all of a client’s property, not only the gardens close to the house but also the driveways, walking paths and distant forested areas. She understood the importance of trees and planned how they would grow and shape the view over many years. This can be seen in the Glade …

and in the view over the countryside.

I have visited only three of Coffin’s many gardens — Winterthur, Mt. Cuba and Clayton, the Long Island estate of Childs Frick, now home to the Nassau County Museum of Art. The formal parterre there which was restored in recent years illustrates her fondness for symmetry and balance, particularly through the use of circular shapes.

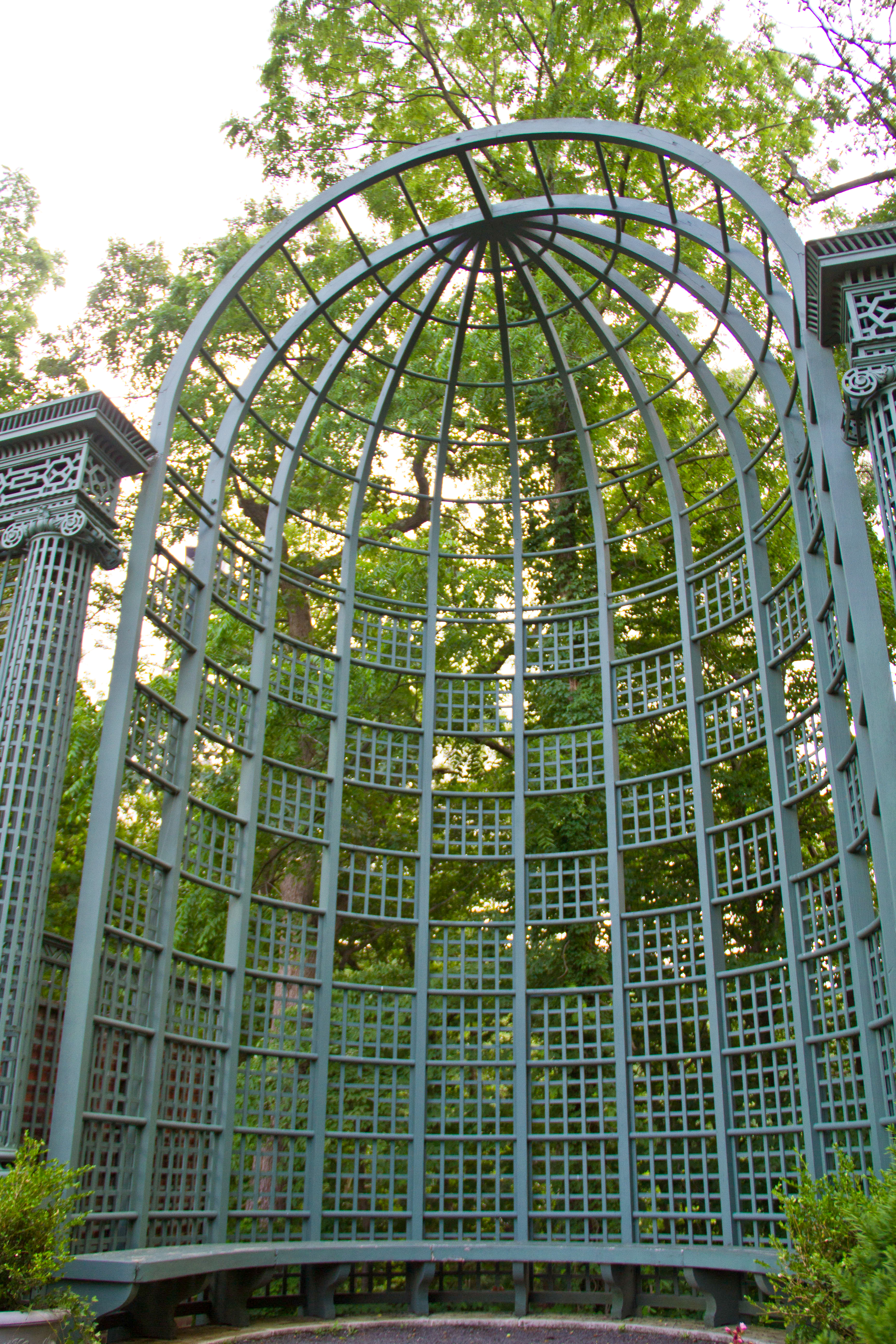

This shape is echoed in the beautiful teak trellis at one end of the formal allée, also recently restored.

While Coffin favoured formal designs, she tended to pair plants within them in more daring ways, letting them grow wildly. One of my photographs from the Nassau County Museum garden gives some sense of this.

So does a contemporary planting from Mt. Cuba, the Delaware garden of Lammot du Pont Copeland and his wife Pamela.

.

Mt. Cuba is now known primarily as an innovative garden specializing in wildflowers of the mid-Atlantic region, and this great interest of the Copelands is now seen to best advantage in the woodlands surrounding the house. Following World War II, they invited Marian Coffin to complete the formal design laid out earlier by Thomas Sears. Her Round Garden, designed in 1949, contains seasonal displays of annuals and perennials. Surrounded by tall clipped evergreen shrubs, its centre is a pool shaped like a Maltese cross.

My only photo of this area shows the brick work, shrubs and one edge of the pool.

From 1918 to 1952, Coffin was the University of Delaware’s landscape architect, a position that required her to unite the university’s two separate campuses (the former Delaware College to the north and the Delaware Women’s College to the south) into one cohesive design. Once again a circle was her solution. But the effectiveness of her design is not the only thing worth noting. Her role with the university itself is significant since she and her contemporary, Beatrix Ferrand, were the only women of their era hired in this capacity; other women landscape architects were confined to designing residential gardens.

One of her often-cited works is Gibralter, originally the home of Hugh Rodney Sharp and his wife, Isabella Mathieu du Pont Sharp. After being restored by Preservation Delaware, the gardens are now public and open year round, offering the closest recreation of Coffin’s overall vision. A series of terraces lead from the house on the top of the rocky hill down to a flower garden. A curving marble staircase connects the terraces, each with a unique theme, allowing visitors to move through a colourful arrangement of flowers, shrubs, and trees. Statues from all over the world have also been restored and a large tea house provides a viewing spot onto flowering bushes planted along a row of cypresses.

As the Gibralter website points out, the re-named Marian Coffin Garden “not only represents part of the historical heritage of Delaware, but the passion and diligence of a woman struggling to break free of standard gender roles in pursuit of her dream.”

Marian Coffin as a young woman, photo courtesy of the Cultural Landscape Foundation

Though perhaps less well-known today than her contemporaries, Beatrix Farrand and Ellen Biddle Shipman, Coffin was appreciated during her lifetime for her refined and elegant designs, both formal and naturalistic. She was recognized by her peers in 1906 when she was accepted as a Junior Member of the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA), and again in 1918, when she was made an ASLA Fellow. Her career as a practicing landscape architect lasted for 53 years, until her death. As one of the first generation of women to break into a largely male occupation, she deserves to be remembered and honoured, both as a designer and as a pioneer.