This year, the Chelsea Flower Show celebrated its 100th birthday. To mark the event, the organizers broke a long-standing rule and allowed garden gnomes to appear. Celebrities like Elton John decorated and raffled gnomes to raise funds for the Royal Horticultural Society. It was a publicity stunt that worked. This year’s show attracted even more attention than normal, because gnomes were there.

|

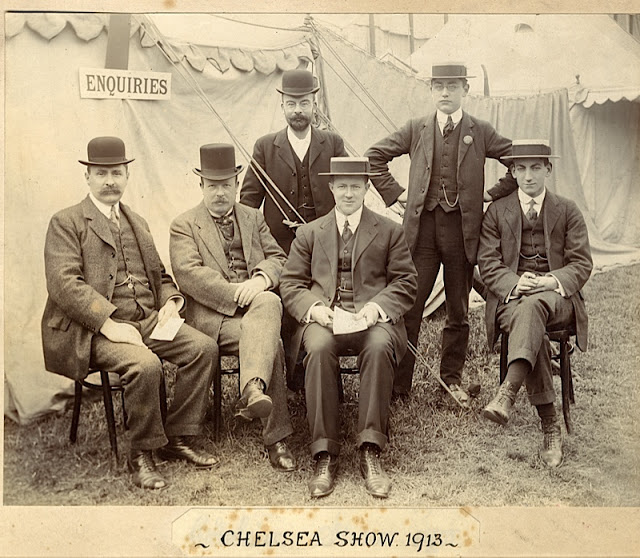

| This on-line photo was not identified, but surely at least one of these spectators is a royal. |

It’s ironic. The Chelsea Flower Show is an upper class affair, frequented by royalty and celebrities as well as RHS members and ordinary gardeners. Garden gnomes were banned 100 years ago because the organizers said they spoiled good garden design.

What they meant was, gnomes were too popular.

Ordinary gardeners liked them, could afford them, and used them. They were no longer fashionable. They were in bad taste.

That wasn’t always the case.

|

| RHS Staff at the 1913 Chelsea Flower Show |

Garden gnomes first appeared in England in 1847, in the upper class garden of Sir Charles Isham. (One source says he was a vegetarian spiritualist and was hoping the terracotta gnomes would attract the real thing to his garden. Maybe, maybe not.)

Sir Charles brought 21 gnomes to Lamport Hall in Northamptonshire and installed them in his rockery. At the time, and for the next fifty years, both the rockery and the gnomes were highly praised.

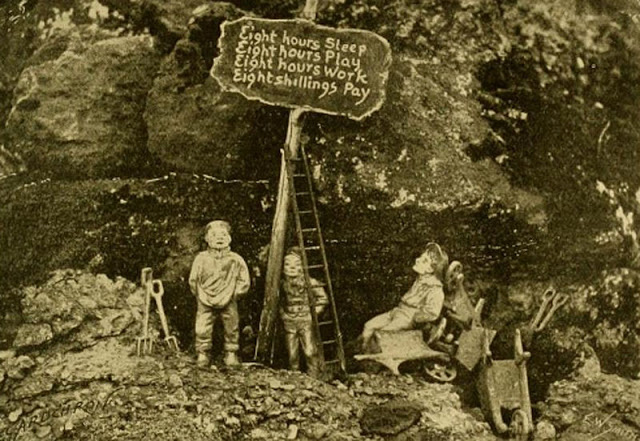

“The caves and recesses with the fairy miners are another distinctive feature. These miniature figures (only a few inches high) are in various attitudes and in strange association with the dwarf trees. In one section they are on strike, hands in pockets, with a general aspect of disdain and indignation.”

|

| Mining gnomes at Lamport Hall. The photo is from the1890s |

Fifteen years after the last favourable review appeared, The Chelsea Flower Show made its debut. From the beginning its ruling was firm: no gnomes allowed.

Garden snobbery still exists. It’s easy to turn up a nose at a garden stuffed with ‘stuff,’ like the one below that I saw in Normandy, France.

|

| Two gnomes, two bathtubs, two cherubic children and one plastic dog make a tableau in a French garden. |

I came across the gnome below in a botanical garden in Naples, Florida. I was surprised: it wasn’t what I expected to see in such an up-market location. Then I realized the gnome was there to attract children. He was planted just outside an enclosure where butterflies fluttered freely. The butterflies brought families to the botanical garden, the gnome was a nice added touch.

|

| Is this gnome holding a mushroom or a butterfly? |

Walt Disney’s “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” popularized gnomes in North America in the 1930s. Along with gnomes came wishing wells, concrete fairies and lawn jockeys. I doubt these objects were ever popular among a North American gardening elite, any more than gnomes were at Chelsea.

Taste, along with humour, is a matter of opinion. I laughed quite genuinely when I saw the shrine below on a roadside in Cold Spring, New York.

|

| Godzilla enshrined |

I loved the humour. Godzilla is not a religious figure. He’s not a 19th century gnome or a Disney-fied dwarf, he’s a 20th century guy out to raise cain. What happened on Sept 18, 1996? It must have been an earth-shattering day for someone. Was it Jed whose world fell apart? And was Jed the shrine-maker or the plastic toy?

After I stopped laughing, I went a short way down the road to visit Stonecrop, the fashionable and tasteful garden of the late Frank Cabot, founder of the Garden Conservancy. There I saw a metal frog lounging in a shady waterside gazebo.

A frog is not a gnome. And yet…

Like it or not, I doubt that anyone would argue that Mr Cabot’s frog spoils the design of the garden. Rather, I think it reflects his sense of humour and the time and place in which he lived. Godzilla made me laugh. The frog made me smile, a tad condescendingly. He made my companion demand to have her photo taken beside him.

A side tangent to your post, Pat, about the godzilla shrine: when I saw the date and the name, I suspected it of being a memorial, possibly for someone who died in a road accident. A little Googling revealed it commemmorates a boy who died at 17, who loved dinosaurs: http://moderndinosaur.wordpress.com/tag/jed-dellarmi/

Also, I love that giant frog!

A big thank you to the reader who figured out the Godzilla shrine. It’s sad to think of this commemorating an accident, and somehow heartening to know that his love of dinosaurs continues to spread joy.

We had a gnome episode at our condo building several years ago. Someone complained about several gnomes adorning a private doorway. Granted, they were, in my opinion, tacky. Not sophisticated nor good design. But they expressed the owner. What about the folks who have nothing outside their door? No personal statement whatever? What does that say? My reaction to the complaint against my neighbor was to put a small gnome in the plant outside my door. Another neighbor, a Harvard-educated CPA, unaware of the controversy, in her innocence placed a LARGE gnome outside her door. Mine is gone, those of the initial offending owner are gone as she moved, but the LARGE gnome remains next door. It is not stylish but the owner likes it and I rarely walk that way. Interesting that a gnome can be so controversial while a Chinese Ho Tai (is that redundant?) is not. Many people place Buddha figures on the ground, which is incorrect. The figure should be above the heart. It pains me to walk through garden statuary shops. When does whimsy become offensively trite?

Metal frogs, on the other hand, never go out of style.

What a saga! Sharing a building has its ups and downs, for sure. We live in a condominium in Montreal, and the rules governing behaviour are strict — ridiculously so, in some cases. Gnomes are not mentioned… Metal frogs? I prefer metal rabbits. My favourite ornament, though, was the bobbing owl we once had on the dock at the lake. It did its job, keeping the dock and diving board seagull free — for a while, at least.