England has many fine gardens. Houghton Hall in Norfolk is one of the finest, offering a stimulating combination of horticulture, contemporary art and history that is far too much to absorb in a single visit.

The most popular part of the garden is the five acre Walled Garden. Divided into contrasting areas, the Walled Garden contains a double-sided herbaceous border, an Italian garden, a formal rose parterre, fruit and vegetable gardens, a glasshouse, a rustic temple, antique statues, fountains and contemporary sculptures. With so many aspects, the area could feel muddled or over-crowded, but a strong geometric structure holds the disparate elements together with ease.

The long double herbaceous border wasn’t at its peak when I visited last September but it still held enough interest to elicit a wow or two.

The fading nepeta contrasts with vibrant dahlias. What do you think — are the wooden tutors a bit heavy or are their proportions a good balance for the space?

Dahlias of all types featured prominently, in this border and in another dedicated exclusively to the plant.

I like the shape and colour of this flower. It almost tempts me to grow dahlias — but then I’d have to dig the tubers annually and overwinter them. Is the work worth it?

The double border stretches across the entire width of the walled acreage, with a well-proportioned rondel at the mid-point to mark the intersection of the two main paths.

The rondel, defined by curved hedges, is halfway along the path. Barely visible in the distance is a temple designed by Isabel and Julian Bannerman.

Drawing you down the path is the structure at the far end. A garden folly, typical of the work done by Isabel and Julian Bannerman, links the contemporary garden with the history of the property and with 18th century English garden design, when allusions to Greece and Rome connected the growing British empire with those of ancient times.

Massive tree trunks form columns and antlers from the estate’s herd of white deer provide texture and detail in the pediment. Two chairs offer a place to sit and enjoy the view back into the garden.

A formal rose garden, well past its best before date when I visited, anchors one quadrant of the garden.

Classical statues towered above what must be a splendid display in season. The curving yew hedges offered a nice contrast to the formality of the enclosed beds.

A Mediterranean garden tucked into a smaller space provided a quiet resting spot on a warm day.

Well-trimmed boxwood edged the gravel paths. There were no signs of box blight.

Its central water feature also offered an interesting contrast to Jeppe Hein’s contemporary sculpture located nearby.

“Waterflame” is an intriguing work that combines the contrasting elements of water and fire.

The Marquess of Cholmondelay, owner of Houghton Hall, has installed many fine pieces of contemporary sculpture since he succeeded to the title in 1990. I saw four works by Sir Richard Long, including “Houghton Cross” which was laid out in the Walled Garden on a former croquet lawn.

The ‘ancient worthies’ references found in the Bannerman temple were repeated with busts partly hidden in niches in the hedges surrounding this former croquet lawn.

The Walled Garden was impressive in its scale and variety but the high point of the garden for me was the contemporary sculpture by James Turrell. It’s hard — perhaps impossible — to capture the nature of this work in photos, because of what it is in itself, and because of how it is situated.

This map of the property gives a sense of scale. The 5-acre Walled Garden is on the right, the wilderness area on the left. Separating them is the Hall itself and the spectacular open area that sweeps out in front of it.

First, imagine leaving the Walled Garden, walking through the Stable Block and along a memorial pathway to reach the Hall itself, a Palladian masterwork built in the early 1700s for Britain’s first Prime Minister, Sir Robert Walpole.

Sculptures by Damien Hirst were an irritating distraction, interfering with the classicism of the Palladian facade

Imagine turning your back to the Hall and looking out onto a long allée, a broad, grassy tree-lined walk simple in concept but enormous in scale, that dips and rises and stretches out to a distant tomorrow.

The grass ‘path’ runs the width of the Hall and its colonnades before narrowing to a central allée flanked by a double line of trees, trimmed to perfection.

Then walk beyond formality into a forested area, seemingly wild. There, open a gate and walk along a path lined with cloud-pruned boxwood.

A winding path leads through amorphously-shaped boxwood to what seems an insignificant building in the background.

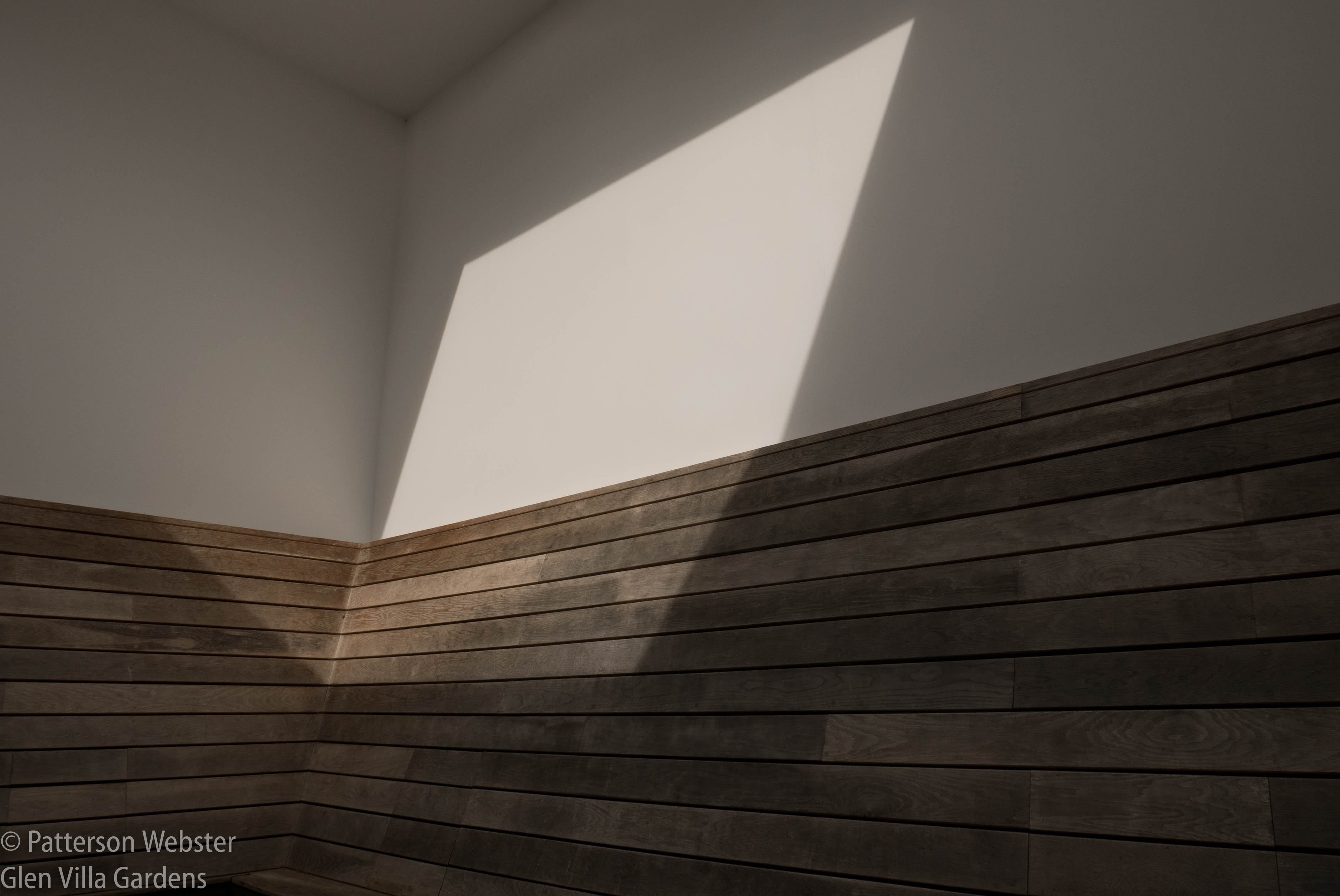

Follow the path to enter a simple wooden structure, cube-like, with benches along the sides. Sit down and begin to breathe. Take in the calm.

‘Skyspace: Seldom Seen’ is a work of art by the American artist James Turrell.

Look up.

An opening in the roof focuses the view on the sky.

Above is the sky, nothing more. Yet so much more.

I visited Turrell’s Skyspace: Seldom Seen on a cloudy day. There was little contrast in colour as there must be in sunnier times, when the sky is blue and clouds pure white. But this did not interfere with an experience that was overwhelming in its intensity. As I sat and watched, the sky changed. I was a child, stretched out on the grass, mesmerized, watching the world shift and change, imagining whatever I wanted to see and whatever I wanted to be.

Shifting shadows on the wall brought the experience closer to the ground.

I spent a long time at Skyspace, and would have spent more, had time permitted. But there was more to see, including sculptures by Richard Long and others.

This sculpture by Richard Long, titled “Full Moon Circle” is located partway down the long walk in front of the Hall.

Tucked into the woods was “Scholar Rock” by the Chinese artist Zhan Wang.

Many of Zhan Wang’s sculptures are similar to this one, large highly textured rock-like pieces coated in chrome. In Chinese culture, Scholar’s rocks are said to possess the purest form of vital energy and are often found in traditional Chinese gardens.

I’m not a fan of Damien Hirst, probably Britain’s best paid and best-known artist, who was chosen as this year’s featured artist in Lord Cholmondeley’s program “Artlandish.” Michael Glover, art critic for the Independent, described the sculptures as “fairground-freaky, upscaled giants.” I agree. Their size, however, did work in the expansive grounds.

These pieces by Damien Hirst made me think of medical models with interior body parts exposed.

There was much I didn’t have time to see or appreciate at Houghton Hall — sculptures by Rachel Whiteread, Stephen Cox, Phillip King and Anya Gallaccio. (I was particularly disappointed to miss Gallaccio’s Sybil Hedge, purple beech hedges laid out in the signature of Sybil Sassoon, grandmother of the current Marquess and the woman responsible for rejuvenating the garden early in the 20th century. ) Toy soldiers aren’t my thing, but Houghton’s collection is fascinating, I’m told. And the interior of the house contains fine works of art and magnificent state rooms decorated by William Kent.

Often I want to visit a garden for a second or a third time. The range of things to see at Houghton Hall is so grand that I’d need a third, fourth or fifth visit to see and appreciate all it has to offer. I hope the opportunity arises.