Memorials are tricky things to get right. In the past, when heroes were celebrated and the power of rulers was exalted in monuments that forced ordinary people to crane their necks skywards, understanding a memorial was easy. A man on horseback was a triumphant military leader. A statue elevated on a Greek-style plinth was a politician, or perhaps a king or queen. When the statue was part of a fountain or surrounded by figures of reclining women in various stages of undress, the message was probably one that celebrated the achievements of a country or the triumph of one group over another.

This figure is part of the Governor Phillip fountain in the Sydney Botanical Garden in Australia. This figure represents Agriculture. Other figures represent mining, commerce and navigation. Much smaller are four bas reliefs of Aborigines.

In today’s more cynical world, designing a memorial that honours an individual or an event of significance in a way that isn’t trite, sentimental or self-congratulatory is more difficult. There are successes: Maya Lin’s Vietnam War Memorial comes to mind immediately, as does Peter Eisenman’s Holocaust Memorial in Berlin. These succeed through a simplicity that touches the emotions. But the controversy surrounding the design for the 9/11 memorial in New York City suggests that a memorial which uses abstract and unfamiliar symbols isn’t as easily understood or appreciated by many. And because of that, it may be disregarded or dismissed.

The memorial to John F. Kennedy at Runnymede was designed by Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe, a man considered one of, if not the, most celebrated British landscape architects of the 20th century. The Kennedy memorial is often described as his masterwork. It was built on land given to the United States by Queen Elizabeth II, an act so unprecedented that it required an act of Parliament, and dedicated by her in 1965, a few short years after Kennedy’s assassination.

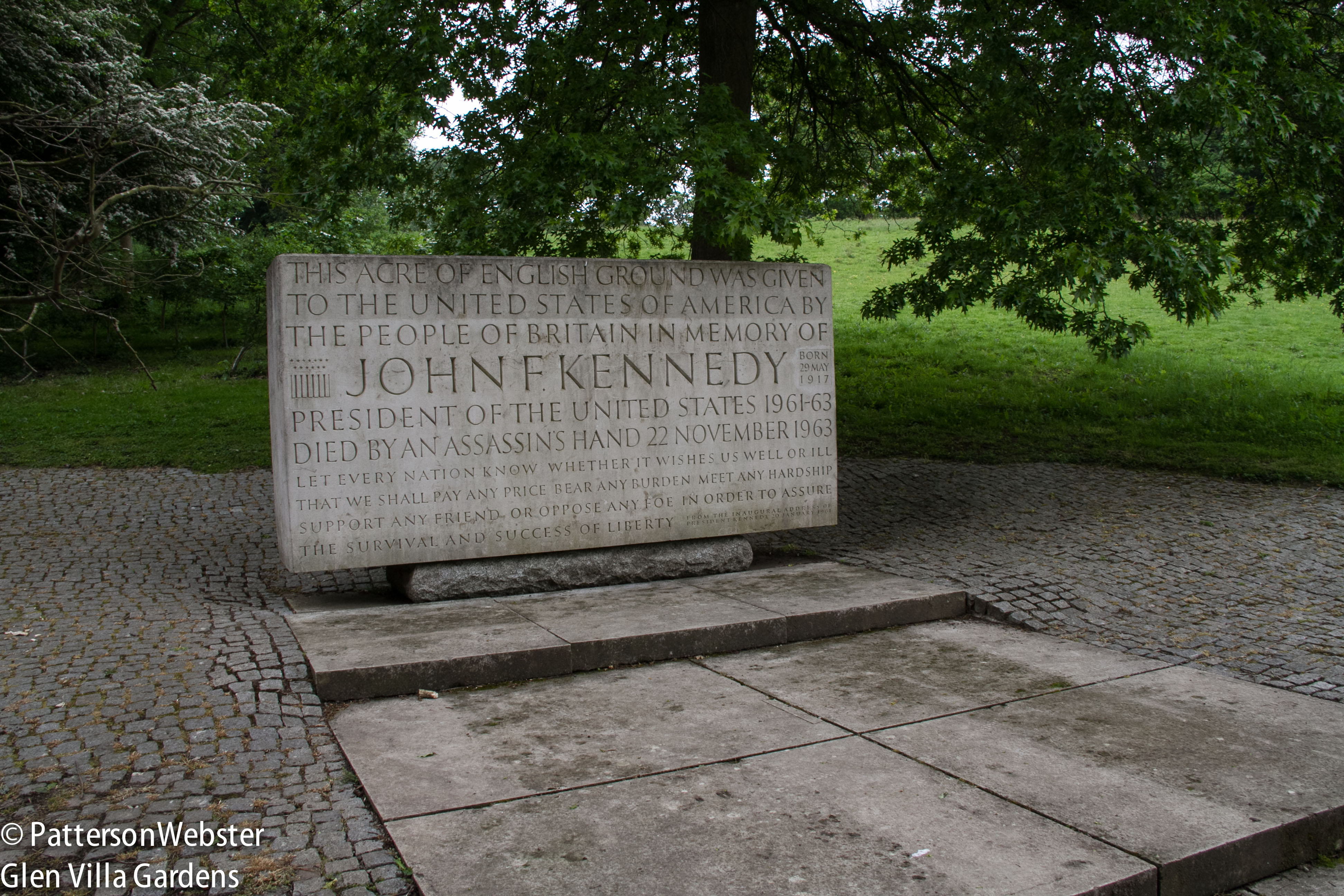

The Kennedy Memorial is not a traditional memorial, although it does include a stone inscribed as a tombstone might be, with words from Kennedy’s 1961 inaugural address. But the stone is not the central feature, it is simply one element in a landscape designed with symbolism in mind. The important element, the thing that makes this memorial special, is what the visitor brings to it. It is the experience of the visitor herself, the journey through space, from dark to light and from movement to stillness.

Describing what happens is simple if the description is kept to the facts alone. When I visited the memorial this week, on a cool, grey morning, I walked across an open meadow on a mown path that follows the track set by thousands of other visitors. I climbed a hill through the woods. At the top I saw a large engraved stone. I followed a path along the side of the hill to a stone bench where I sat and looked out over the meadow below and the busy road that runs through it. Then I retraced my steps and got back on the bus.

Mown paths offer the visitor a choice. Shall I go this way or that?

Describing the experience and what I felt is more difficult. When I came to the wicket fence I began to climb a hill on a path that led through a natural woodland. The path was made of granite stones, or setts. Because the setts were laid directly on the earth, the surface was uneven, with small variations that echoed the variations beneath. The setts were edged with cobblestones that widened or narrowed for no apparent reason, as ripples might move in a stream because of something hidden under the surface.

A river of cobblestones surrounds an uneven, curving path.

The steps were made of the same granite setts as the path. They were also uneven, sometimes wider, sometimes shallower, in response to the slope of the hill, and they curved almost imperceptibly.

The front edge of each step is uneven. Each step is different, and each sett is unlike the others.

From my reading I knew there were 50 steps, as there are 50 U.S. states. I knew that each step was different and that there were 60,000 setts, representing the multitude of pilgrims who would find their way to the path. I knew that the walk was meant to connect me to the journey made in John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, and that the dark woods surrounding the path to remind me of Dante and the opening lines of The Divine Comedy, where Dante says that “in the middle of our life’s journey, I found myself in a dark wood.”

Knowing all this was, for me, interesting but essentially irrelevant. The walk was the thing. The woods were beautifully natural, making the walk a pleasant experience. The detailed thought behind the design of the steps intensified the pleasure I was feeling as did the way the woods were cared for, with fallen tree trunks left to rot on site, to provide a place for ferns and moss to grow.

What I discovered, though, was that the climb to the memorial stone led me on a personal journey — which I believe is what Jellicoe intended. It led me back in time and inwards, to the self I was when Kennedy was killed. Memories flooded in, unstoppable.

The stone is curved in all directions. Sitting on a rough block of stone, it seems to float in the air.

The memorial stone is a huge block of Portland stone, a limestone dating from the Jurassic period. The age of the stone underlines the weight of history that permeates the site. The fact that the same stone is used for many major public buildings in London, including St. Paul’s cathedral and Buckingham Palace, subtly reinforces the connections that link England and the U.S., which so shortly after World War II were particularly strong.

The inscription on the memorial stone isn’t arranged in lines as inscriptions usually are. Instead the words are spread across the whole surface, almost as if the stone itself is speaking, of liberty and the sacrifices necessary to ensure that it continue.

“Let every nation know, whether it wishes us well or ill, that we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend or oppose any foe, in order to assure the survival and success of liberty.”

At Runnymede, the survival and success of liberty acquire a special meaning. After all, it was here, in 1215, that King John signed the Magna Carta, the document that is the foundation of the freedom of the individual against the arbitrary authority of a ruler.

In front of the memorial stone the branch of a hawthorn tree extends over the path, forcing a visitor to bow slightly to approach. Chosen by Jellicoe to symbolize Kennedy’s Catholicism, the tree for me was another symbol connecting the two English-speaking countries — hawthorns were blooming wildly all around, in hedgerows and on highway verges throughout the area. Behind the stone was another symbolic choice, a red oak. A native American species, this oak comes into full colour in the fall, when Kennedy was shot.

Legend says that all the hawthorn trees in England descended from the hawthorn staff planted at Glastonbury by Joseph of Arimathea, the man who gave his tomb for Jesus’s burial.

A formal stone path leads from the memorial stone across the side of the hill to two stone benches set into the hillside. Jellicoe called these benches the Seats of Contemplation. They are larger than normal and sitting on them on a cold morning was not a comfortable experience. I was with a group of people, most of whom found this part of the memorial disappointing. The path and the benches seemed to them a let-down, an afterthought not fully developed.

The uneven edge of the path suggests the crenallations that would be found on a fortified castle from the period of the Magna Carta . The swooping curves of the mowing pattern are a decorative touch that I hope will be discontinued.

For me, they were the final part of the experience. The path leading up prepared me to look inwards; the Seats of Contemplation forced me to look outwards, to face the world I lived in now and to consider how the passage of time had changed it and me. The benches offered as well an opportunity to stop moving, a place to sit and be still, to look and to contemplate.

In a group, stillness and contemplation are difficult. Even so, retracing my steps, I saw the same things from a different angle. The woodland hadn’t changed. Nor had I in any significant way. But the experience lingers.

Jellicoe aimed to design a memorial that incorporated universal principles — life, death, spirit. I believe he succeeded.