Kiftsgate Court is one of those English gardens included on many garden tours, in part because it is so conveniently located, just down the road from Hidcote, the iconic garden created by the Anglo-American Lawrence Johnston. The gardens at Kiftsgate were created over the last hundred years by three generations of women — grandmother, mother and daughter — each of whom made her own contribution to the garden as it is today.

Renowned for the Kiftsgate rose, the garden contains some wonderful areas and some fine plantings, with sumptuous flowers like this one that I photographed on a visit in 2012.

Oh, my. That is luscious flower power.

Flowers of all sorts along with rare and exotic plants enliven the garden in every season.

Asters and sedum: a nice colour contrast.

The handsome house is flanked by a four-square entry garden and terrace on one side,

The classic façade that rears up above the entry garden was actually brought in from a local village and erected here piece by piece.

and by a sunken courtyard with a white garden on the other.

Kiftsgate blue chairs match the colour of the sky on the day I took this photo.

The stand-out in this area is a gorgeous well head, carved according to the garden’s website with “bucolic activities” including harvesting, hunting and wine making.

The lowest band of carving shows a bird piercing its own breast to feed its young. This symbol was commonly used in medieval times to suggest Christ’s sacrifice on the cross.

Some may argue that the blue chairs and other contrasts in colour in parts of the garden are a bit strong; others will find them exactly to their taste.

What do you think — is there too much colour contrast or just the right amount? Or maybe not enough?

The debate about this garden isn’t limited to contrasts of colour. Much about this garden comes down to questions of taste. Some people may like the art in the garden… this curvaceous lady at the end of a long path ….

This sculpture of a seated woman whose lap becomes a seat is by Simon Verity. It was commissioned by Diany Binny, the second of the three generations of women who designed the garden.

or this motherly figure who stands beside the path to the lower garden.

A sculpture of mother and child fits into the real life story of this garden designed and gardened by grandmother, mother and daughter.

Pablo Picasso is widely quoted as having said that “good artists borrow, great artists steal.” The same can be said of gardeners. Inevitably, a stolen idea is transformed and becomes your own when you ‘steal’ it. This is certainly the case at Kiftsgate. Some years ago, the tennis court was converted to a water garden, using Geoffrey Jellicoe’s Jungian-inspired design from Sutton Place in Surrey. I have no problem with that.

Using green, white and black only provides a strong contrast to the wide range of colours used in the rest of the garden.

But something significant was lost in the process. The stepping stones that cross the moat at Sutton Place carry a symbolic message — they are the first steps in an allegorical journey through time. The steps at Kiftsgate lead to an island which goes nowhere; to get off the island you must retrace your steps.

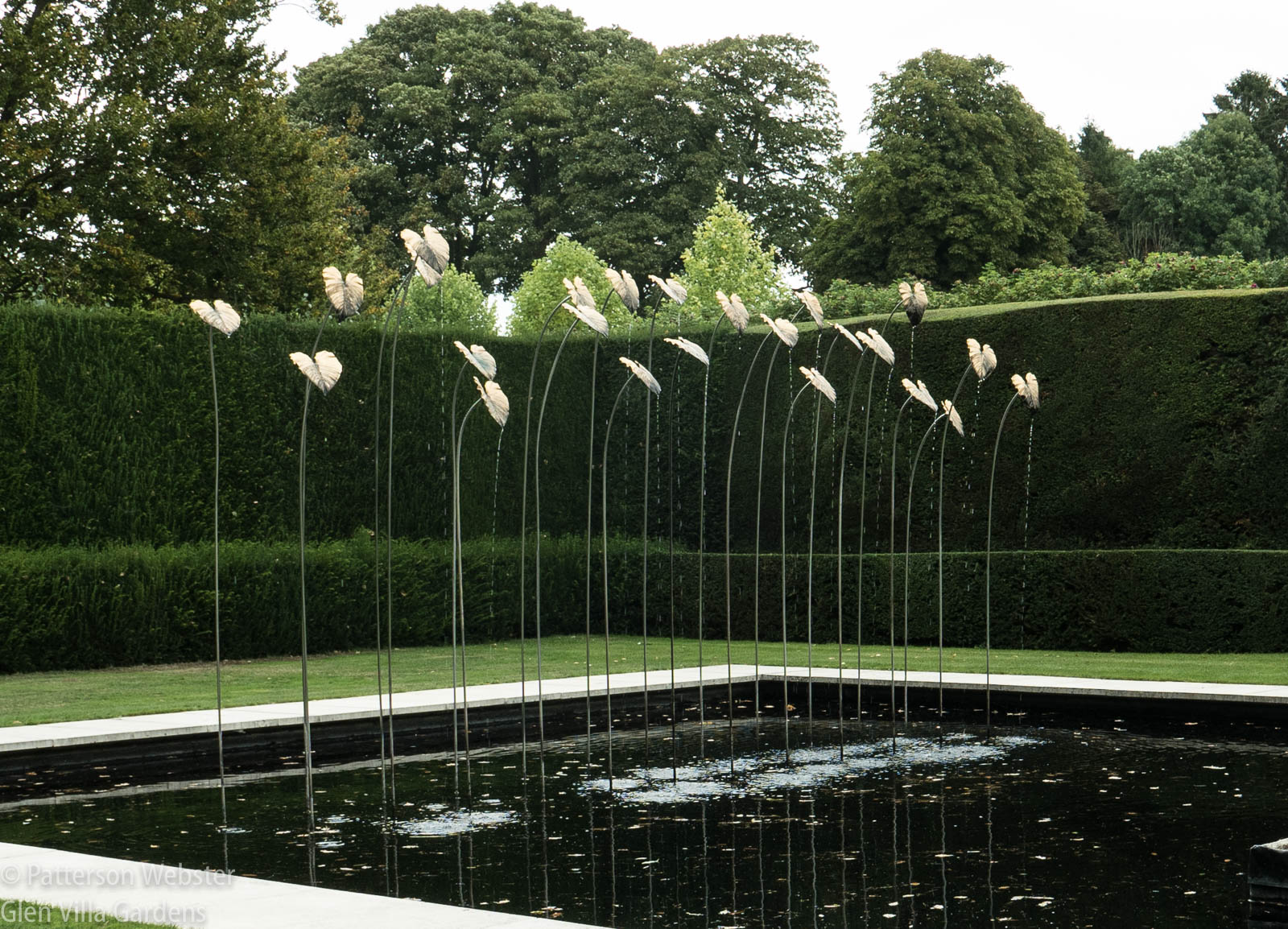

This modification changes a meaningful element into something purely decorative. I wouldn’t necessarily quarrel with that change — the resulting design still conveys a sense of calm, reinforced by the restrained colour palette. But Sir Geoffrey’s design has been modified as well by the addition of gilded bronze leaves that stand above the water on thin rods that move in the breeze.

On one visit to Kiftsgate, water tinkled off the leaves into the water. Another time, the leaves were dry.

I greatly prefer both the clarity and originality of Jellicoe’s design and find the wobbly leaves a distraction. Others may disagree.

Opinions converge, though, when it comes to the latest addition to the garden at Kiftsgate. Everyone in the group I was with in 2018 disliked what they saw, as did everyone I spoke to in the garden at the time and later.

The curved benches are by Nicky Hodges.

Creating the Jellicoe-inspired water garden involved removing nearly 1000 tons of soil. That soil was then moulded into a horseshoe-shaped mound and a long allée of tulip trees was planted. But what to do with the area inside the horseshoe mound? Someone decided to fill it with grey gravel and to add a chevron pattern of coloured stones that points along the allée towards a sculpture in the distance.

Visitors walk through an orchard and climb steps on the outside of the mound. At the top, above the benches, they get their first glance at this newest addition to the garden.

Seeing this addition was a shock. Nothing about it appeals to me. The grey gravel and coloured stones feel very much out of keeping with a garden focused on colour and on rare and exotic plants. And why the potted olive trees? Combined with gravel they might be intended to suggest a Mediterranean garden but in this context they feel both extraneous and incongruous.

The olive trees may be fine specimens but do they relate to anything in the larger garden or in this section of it? Or are they left-overs from someplace else?

I love a good allée of trees and tulip trees are a favourite. But for an allée like this one to be fully effective, the trees need to be planted on level ground, not on the side of a slope.

The pronounced slope of the hill makes me feel off balance. I want to straighten it up!

I didn’t walk to the end of the allée so I can’t comment on the sculpture that is the allée’s focal point and destination. From a distance it feels insubstantial, not nearly strong enough to create the visual impact that is needed. Up close, it may be different.

I cropped a photo to show this semi-close up of the sculpture by Pete Moorhouse.

Somewhere I read that Diany Binny’s motto proclaimed that the “art of gardening is to notice.” I heartily agree. To notice is to admire the ancient stone that ornaments the garden and reluctantly to accept the necessity for the artificial grass that now surrounds it, due to excessive foot traffic. To notice is to admire the self-seeded flowers whose colour contrasts so nicely with the rough stone wall…

The yellow and orange petals shine like little light bulbs.

or the rosehip-like shape of a medlar, a fruit I’ve rarely seen and have never eaten.

The fruits of a medlar are hard and acidic, according to Wikipedia, but become edible after being softened by frost or if left long enough in storage. Apparently the inside is similar in taste and consistency to applesauce.

But to notice is also to remark on the uncomfortably harsh geometry of the chevron design. It is to acknowledge the discolouration on the white stones and the bare grass on the sides of the mound.

What do you think? Thumbs up or thumbs down?

It is to question whether the avenue, the mound and the sculpture are worthy of the garden as a whole.

In a world where garden critiques are far too often eschewed, I’m sticking my neck out by stating my opinion so clearly. I welcome comments on the other side.