I spent Easter weekend visiting Washington D.C. with my husband and my sister. We were hoping to see cherry blossoms colouring the sky but it has been too cold and the buds are only now beginning to open. So no photos of pink blossoms, although the photo below shows how gloriously bent and mis-shapen the trees are, monuments to time and the up-keep provided by the National Park Service.

|

| Cherry trees beside Washington’s Tidal Basin |

Instead of admiring cherry blossoms, we visited museums and two of Washington’s newer memorials.

Washington is chockablock full of monuments, memorials and other testaments to history. There are big tall monuments like the Washington Monument, whose needle poking the sky is visible from

most of the central part of the city. (Completed in 1884, it was repaired two years ago and is under repair again, following an earthquake in 2010.)

|

The Washington Monument with scaffolding,

mirrored in the Reflecting Pool |

There are square monuments like the Lincoln Memorial, domed and columned ones like the Jefferson Memorial, curved ones like the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. And there are smaller and newer ones whose forms are not yet iconic reminders of events (and movies) that shaped our lives.

One of the newest is the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial, completed in 2011. Standing near water’s edge, across the Tidal Basin from the Jefferson Memorial, this 4-acre commemoration is roughly fan-shaped. Located symbolically at 1964 Independence Avenue, the year the Civil Rights Act was adopted, it is separated from the street by a curved black wall inscribed with some of Dr. King’s memorable words. Between the wall and the water stands the memorial’s centrepiece, an oversized representation of the man himself, emerging from a block of solid granite.

At first glance, I thought I was seeing Mao Tse-tung. I think the monumental quality of the statue caused my reaction – Dr. King is a whopping 30 feet

(9.1 m) tall – and larger than life statues of Mao were part of the everyday landscape when we lived in Beijing in the late 1960s. The face, too, with its heroic cast, reminded me more of Mao than King. All that was missing was the famous wart.

|

| A granite version of Martin Luther King |

So I wasn’t at all surprised to learn that the artist, Lei Yixin, was Chinese, and that he has carved Mao and some 150 other public monuments. I was surprised, however, to learn that the blindingly white granite came from China, and that the statue itself was carved there by Chinese artisans.

Perhaps this wouldn’t bother me if the overall design worked. But I found the message of the memorial muddled, both by a confused conception and by the materials used. Is it contradictory for a black man whose career is so intimately linked to his skin colour to be depicted in sparkling white granite? And is he emerging from that block of stone or held back by it, not yet fully formed or free to move ahead?

The memorial, designed by the San Francisco firm ROMA, is based on a line from King’s “I Have a Dream” speech of 1963: “Out of a mountain of despair, a stone of hope.” Words play a major role in the Memorial, since a total of 17 quotations appear, on the massive statue and on the crescent-shaped wall that separates the memorial from passing traffic. ROMA says that the design was inspired by Dr. King’s poetic use of language and metaphorical references to the American landscape. If so, the inspiration failed to inspire.

|

| Martin Luther King, a granite version as Mao Tse-tung |

Visitors entering the memorial pass though a gap in an enormous granite ‘mountain,’ two pieces of white stone that stand like bookends holding empty space instead of books. I suppose you can view this as a gateway to the plaza beyond, but for me the stylized carving made it feel more like an entry to Disneyland. I didn’t want to walk through the mountain, I wanted to climb it, to make some symbolic or actual effort to go beyond, into that promised land.

|

| Entrance to the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial |

|

| A side view of the 30-ft high statue |

Instead, after walking through the gap, I was confronted with what looked like the missing chunk of rock, pushed forward to become the ‘stone of hope’ that King spoke of. I had to walk around the rock to see the man, and had to crane my neck when I got there. This is one tall statue — 30 feet high, compared with Jefferson and Lincoln’s 19 feet. He looks out over the water at the Jefferson Memorial, or, in the interpretation provided by the National Parks Service, towards the horizon and the future. But wherever he is looking, he doesn’t engage me, or with me.

|

| The back side of the mountain |

I liked the open-air setting of the memorial. It seems appropriate for a man whose major moments were outdoors, and much more fitting than a classically-styled and roofed space like those at the Jefferson and Lincoln memorials. I liked the location on the edge of the Tidal Basin, surrounded by newly planted cherry trees which, over time, may soften the glare of the white granite. I liked the views from inside the plaza, particularly of the Jefferson Memorial, which position Dr. King as part of a continuum of history. But the overall plan was neither fully conceptual nor fully literal; instead, it teetered uneasily between the two.

|

| The Jefferson Memorial, as seen from the King Memorial |

The other memorial I saw for the first time was the Korean War Veterans Memorial. Again, my reactions were mixed. I thought the soldiers trooping through a tough juniper ground cover were quite effective. I liked their ghostly quality and their shadowy grey forms and their windblown ponchos, so suggestive of mud and nasty weather. They were too realistic for my taste but for the most part they were not depicted as heroic ideals but as real men slogging their way towards an unseen destination.

|

| Ghostly soldiers at the Korean War Veterans Memorial |

As at the King Memorial, a dark stone wall defined the outer edge of the space, separating the memorial from Independence Avenue and providing a backdrop for the advancing troops. Highly polished, it showed the ghostly faces of soldiers and reflected crowds of lively tourists out on the town on a sunny spring day.

|

The faces of soldiers are etched into a polished black granite wall,

reflecting visitors to the Memorial |

A total failure was the end point of the memorial, where a circular basin is chopped in half by a low stone wall. Presumably the wall references a country that remains divided, but that is far from clear. Is it too early in the season for the pool to hold water? Perhaps. But a design that needs a sign to tell people to stay away is a poorly thought-out design.

|

A waterless Pool of Remembrance,

with a sign (impossible to read in this photo)

telling people to stay out of the water. |

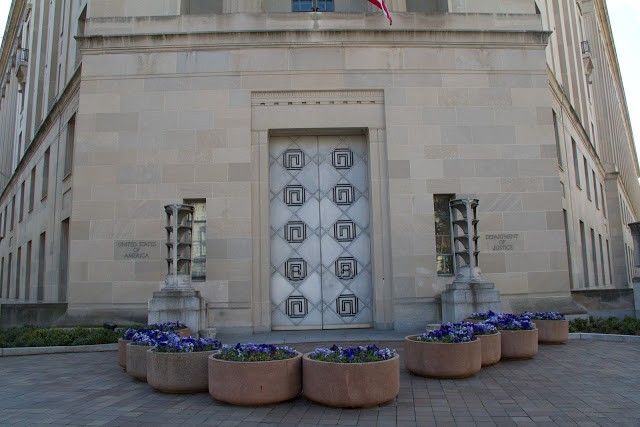

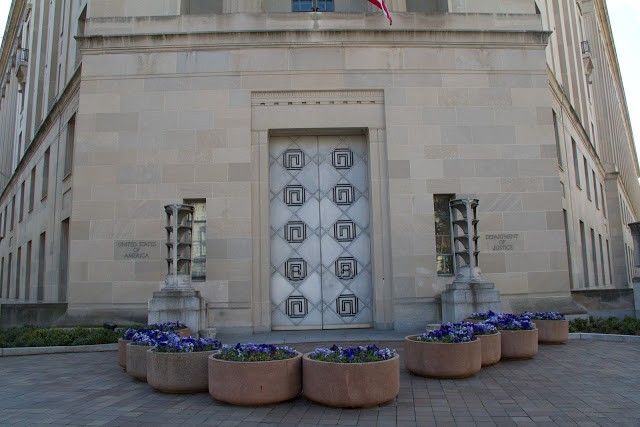

More successful by far were the unintentional ironies of the building that houses the Department of Justice. After visiting the Museum of the American Indian the previous day, I was first struck by the juxtaposition of the words affixed to the stone and the image of the buffalo beside them.

|

| Buffalo appear on the gorgeous Art Deco torchières at the Department of Justice |

The building itself, constructed between 1931-1935, provokes admiration and irritation simultaneously. The doors, a gigantic 20 feet tall, are made of aluminum, as are the Art Deco torchières and other exterior images. The red-tiled roof is wonderfully decorative and the carvings on the pediment an impressive combination of neo-classical and Art Deco styles. I don’t know what the inside looks like – I couldn’t go in. Blocking my way were concrete planters used as stanchions, there to keep justice separated from passers-by. Brutal in size and design, they were full of newly planted pansies.

|

| Pansies protect an entrance to the Department of Justice |

I don’t want to end on a flippant note: the building of monuments and memorials seems too important to dismiss so easily. Memorials are proliferating, at least in the United States. Does this suggest a growing desire to remember, or a growing desire to shape a future memory now, while we can?

Having visited these two new memorials, and holding them in my mind alongside older ones I’ve seen, I am pondering what makes a memorial effective.

The heroic approach of the 19th century doesn’t work anymore. I know this approach well: in Richmond, Virginia, where I grew up, Monument Avenue is a model of its kind, with a procession of Civil War generals offering a paean to the past. Jeb Stuart, Stonewall Jackson, Robert E. Lee: all are shown on horseback, heroic figures, frozen in time. On pedestals high above street level, they are there to be admired. And like the statue of Martin Luther King, their gaze is distant.

|

Robert E. Lee on his horse Traveller,

on Richmond’s Monument Avenue |

I visited Washington’s FDR Memorial some years ago, shortly after it opened, and hoped to visit it again. But time and growing crowds got in the way. What I remember, though, is how I moved through the space. The memorial wasn’t static. There was no bronzed statue meant to be seen from a car, no heroic general gazing into the distance. What there was, or so I remember, was buff coloured stone defining the areas I walked through, room-like spaces that captured different aspects of Franklin Roosevelt’s life. I also remember water that cascaded down a wall, and a sheet of still water that reflected the sky.Moving through the space was as engaging as an immersion. I was forced to be part of the experience rather than to observe it. And so I became engaged emotionally. This happened when I visited Maya Lin’s remarkable memorial to veterans of the Vietnam War. It happened in Phnom Penh at Tuol Sleng prison, and at the World War I Vimy Memorial in France.

So let me end with a question. To be moving, must a memorial involve movement? And does it always have to commemorate war and death?

Great post!

thanks for share..