Are gardens intellectual endeavours or places to soothe the spirits? If a garden is intended to be a conceptual work of art, does it succeed if it has to be explained? And what responsibility rests on the person viewing the garden to understand the ideas that shaped it?

Make the questions personal: should I have to work to understand what a garden is about or is it enough merely to enjoy what I see? If I don’t understand the ideas, on what basis do I judge the garden?

Visiting Througham Court in Gloucestershire made me consider these questions.

One of England’s most unusual contemporary gardens, it showcases the interests and enthusiasms of its owner/designer, Christine Facer Hoffman, a medical scientist turned garden designer. At Througham Court (pronounced “thruff-um”), I saw many objects and sculptures that highlight important 20th-century scientific discoveries: cloning, birth control and genetic sequencing, among others. Fibonacci numbers and risk and probability theories appear on gates, paths and fences. Black holes and concepts of time are explained in the Cosmic Evolution Garden. All of this is presented within the framework of a 1930s Arts and Crafts garden that sits next to a house dating back to medieval times, amidst a gloriously rural Cotswolds landscape.

Traces of the Arts and Crafts garden remain. The drystone terrace, with its semicircular steps sprouting small rock plants, raises visions of ladies in white gossamer gowns. The topiary, the old croquet lawn and the sunken garden near the house underline the feeling of nostalgia that Arts and Crafts gardens so often arouse.

Typical Arts and Crafts semicircular steps full of flowers tucked into crevices lead from one level of the garden to the next.

I visited the garden on a rainy day with the members of the tour I was leading. We entered through a handsome gate called Anatomy of a Black Swan. On the gate a variety of symbols representing risk and probability set the tone for what was to come. (The name of the gate refers to a theory developed by Nassim Nicholas Taleb that describes unexpected events with significant consequences. Events like the rise of the internet, the September 2001 attacks and the 2008 financial meltdown are black swans.)

Just inside the gate was a slightly elevated viewing platform. From it I looked out over the topiary and the drystone terrace, onto the countryside beyond. I tried to avoid looking down at the floor of the terrace, a combination of black, white and red rectangles that to my eyes sat uneasily beside the more familiar traces of the past.

The viewing platform is called the Chirality Terrace, a name that demanded an explanation. Which Ms Facer Hoffman provided. In mathematics, chirality is the property of a figure that is not identical to its mirror image. Chirality also relates to right-handed and left-handed molecules. Hands are an example of chirality: the mirror image of the left hand can’t be superimposed on the right hand, no matter how the hands are positioned.

Mirror imaging plays a big part on the Chirality Terrace. The word itself is spelled out backwards and upside down on a stone pillar; its image reflected in water reads correctly.

Raindrops disturb the reflection in the water, making it impossible to read the word Chirality the right way around.

The word Alice (of Alice in Wonderland fame, honouring the mathematician and author Lewis Carroll) is carved into the tiles, right-side up and flipped down. A profile carved on a bench is repeated, Janus-style.

The letters on the stone wall (shown in the first photo of the Chirality Terrace) are part of a DNA sequence; the formula on the patterned floor shown below alludes to … to what? I can’t remember. But after a lot of poking around on the internet, and with the help of a molecular biologist friend, I learned that the letters and number refer to two forms of a specific amino acid (alenine). The colours have meaning as well: black represents carbon, white is hydrogen and red is oxygen, elements that are the basis of all organic life. The blue that represents nitrogen is shown in the formula’s lettering, and possibly elsewhere.

Fingers almost touch as they do on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. But what do these almost touching fingers mean in this setting?

And what did the outline of a sheep have to do with anything?

The sheep reminded me of the heraldic animals I had seen in the reconstructed Tudor garden at Hampton Court Palace only the week before. Was the link between Tudor gardens and the age of the house? Between the touching fingers, the sheep and religion? But what about the pill? Where did it fit in?

How many sheep do you know that have a black line dividing their bodies in half? Could this be a clue?

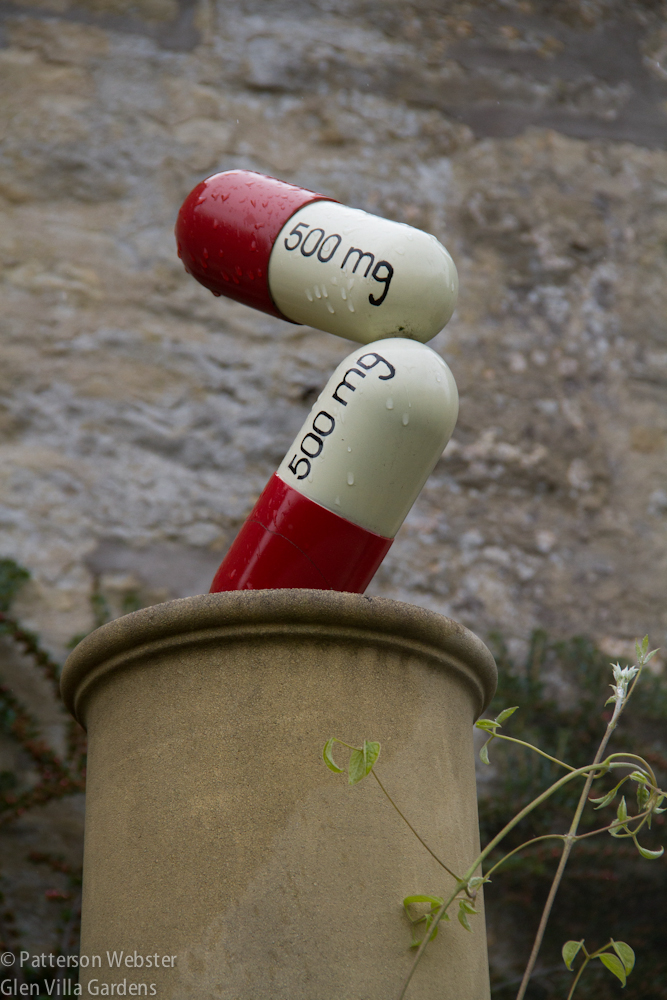

I didn’t ask the questions because the answer was provided before I could think of them. The elevated objects represented significant discoveries made in the 20th century. The sheep is Dolly, the first to be cloned. Another kind of black swan, perhaps.

This blog post isn’t a review of Througham Court as much as a ramble of thoughts about the value of discovering things for yourself. It’s about the joy that comes from investing your time and energy in someone else’s creation. It’s about what a garden is (or can be), about what we expect, and how we react when we find the unexpected.

There were elements at Througham Court that I loved. The path cut through a field, outlined with a simple white line that disappeared over a drystone wall, was a huge success. I appreciated the spacing of the trees planted beside the path. At the far end, two trees were planted a metre apart; the second and third trees were planted two metres apart, the third and fourth trees, three metres, then five, then eight. (Yes, it was a long path.) Because Ms Facer Hoffman had mentioned several times how the Fibonacci sequence of numbers appeared in nature (in the arrangement of sunflower seeds, for example), I could understand the spacing and appreciate how she had, literally, made the Fibonacci sequence visible.

I liked the flags that led my eye down the white-lined path. I liked the grass-covered mound nearby, and the sunburst pool edged with slate that reflected light and shadow in roughly equal measure.

I was amused by the shrubs at the far end of the old croquet court, trimmed to form reclining lounge chairs. I liked the metal pieces that caged the cone-shaped trees, and the skinny trees that reminded me of the flagpoles in the field beyond.

The grass in the old croquet court is mown in strips. From the side the strips looked like waves. I didn’t have a chance to see if the surface was uneven or if my eyes were playing tricks on me.

I liked the fencing that ran around the vegetable garden. Ms Facer Hoffman has a dog named Pi. The fence is topped with the endless sequence of numbers that make up the decimal points of pi. I liked this connection: it was amusing and the fencing was aesthetically satisfying.

Ms Facer Hoffman told us the number of decimal places of pi displayed on the fence, but I don’t remember how many there were. Do the highlighted white number represent the Fibonacci sequence?

The Cosmic Evolution garden was less successful. I liked the plantings and the arrangement of the spheres but, like the Chirality Terrace, the area felt overly contrived.

And yet… After understanding more about the details of the Chirality Terrace, I was impressed by the depth with which Ms Facer Hoffman had explored the concept and made it visible. As I learned more, it became more satisfying intellectually. But it remained unsatisfying aesthetically. The red tiles jarred. They made me uncomfortable. (And I like red.)

I believe that Charles Jencks’ Garden of Cosmic Speculation was the inspiration for this Cosmic Evolution Garden. I may be wrong.

Would I have responded differently to this garden if I had been alone? Would I have taken the time to read the inscriptions under each sphere in the Cosmic Evolution Garden and try to decipher their meaning? Would I have connected the dark pool surrounded by black mondo grass with the idea of a black hole? It’s impossible to say, because I didn’t have the chance.

Only once was I alone in the garden. I wandered into a small area to the side of a path and was captured immediately by the atmosphere. It was quiet and contained and intriguing.

Wooden boards defined a triangular piece of grass. The edging ended in a sharp point, which seemed pointless, and the borders weren’t well planted, but the chance to look and discover something without being instructed made the detour worthwhile. And only now, looking at my photos, do I wonder if the triangular shapes here were meant to recall the triangular trees beside the old croquet court. Were there other triangles I hadn’t noticed?

Ms Facer Hoffman’s garden is a garden of ideas. In the centre of a black bamboo grove, a small table stands on a metal disk. A sentence is written there: Never let your memories be greater than your dreams.

Clearly, this sentiment expresses something important to Ms Facer Hoffman. What, exactly, I don’t know. Certainly her garden does not rely on memories of gardens past. How the scientific ideas she illustrates relate to her dreams is far from clear, to me at least. And what does it matter?

I’d like to return to Througham Court with time to spare. I’d like to explore freely, to reach my own conclusions, in my own time. Would the garden reward the effort? Perhaps, perhaps not. And disappointingly, I’ll probably never know.

But of all the gardens in England I visited last year, Througham Court is the one that continues to occupy my mind. In my books, that alone makes it a big success.

I hope you can get back! How would you see and feel it the next time? Next time I am off chasing rabbits I hope I find this place, amazing!

This is a rabbit hole I would gladly fall through again. I’d love to return. Not sure how I’d respond to the place if/when I do.

It would be your own fantastical world!

When it comes to gardens, I will favor aesthetically pleasing over intellectually satisfying every time. If you have to “get” it to appreciate it, it does come across as contrived. But the lady made the garden for herself. Presumably she “gets” it. Does anyone else really need to, when it is a private garden?

In the context of English gardens, where private is semi-public (or can be), I’m not sure that you can say she made it only for herself. Definitely she ‘gets’ it, though. For me, a point that continues to be unclear is whether the discussion caused by a difference of opinions and reactions to a space in itself makes that garden ‘successful.’ Another way of asking this question: is a garden that everyone sees as ‘good’ or ‘nice’ or aesthetically satisfying a better garden than one that provokes discussion and controversy?

“Are gardens intellectual endeavours or places to soothe the spirits? If a garden is intended to be a conceptual work of art, does it succeed if it has to be explained? And what responsibility rests on the person viewing the garden to understand the ideas that shaped it?”

Such an interesting assertion and debate, that applies to all art and creativity. This is clearly a much loved garden and considering how many gardens are pretty without saying anything at all, it’s interesting to come across one that wants to convey ideas, even though you found it hard to discern which ones and query how it’s done. To try to capture scientific ideas with horticulture is a challenge not many people even think of trying to do. Is each feature merely illustrating science or adding something to the concept? Imagine if all there were in ths garden were the pretty corners and vistas, such as those dry stones with the pink and white plants. So many gardens are attractive but few try to say anything. So many attractive houses have gardens that are frankly interchangeable, whether professionally designed or not.

It’s like the conundrum about paintings and drawings. If a picture needs a written statement or if we’re uncomfortable until we know the title, what does that say about the ability of the painting to convey something to us or about our ability to engage rather than passively look?

Btw I have to admit that my own garden is neither pretty nor interesting and though I know I want non-plant features I’m finding it hard to identify exactly what.

A thought-provoking response, Norma. Much contemporary art requires a level of personal engagement that some people find daunting — it puts genuine responsibility on the viewer to figure out what is going on in the artwork, and why. Througham Court is a daring work of art, and one where the level of viewer responsibility is particularly high. Her choice of science as the motif of the garden challenges visitors. It transforms an ordinary garden visit into a tour of discovery — appropriately, since discovery underpins science itself. Finding a way to make gardens more than pretty isn’t easy but I think it is worth the effort. I hope you discover what non-plant features work for you. Christine Facer Hoffman is a scientist and her investigation of science through the garden gives it a very personal touch. So some unsolicited advice: look to the personal and use that in your garden.