What can we say about 2020? Queen Elizabeth’s Annus Horribilis comes to mind. So does the subject of ruin — personal and business ruin, political ruin and the final ruin, death, which came this year for hundreds of thousands of people, more than we imagined possible when the pandemic began.

But, Janus-like, ruins have a positive as well as a negative face. It may seem contradictory but history and the evidence of my own eyes tell me that to contemplate ruins is to contemplate the future as well as the past.

At Painshill, an early 18th century English garden, the eccentric owner Charles Hamilton constructed a Mausoleum in the form of a ruined Roman triumphal arch. Passing through this ‘arch of death,’ as he called it, contemporary visitors would emerge on the sunny banks of the River Mole, where they would see Hamilton’s newly constructed waterwheel, a revolutionary device that generated electric power and offered a forecast of what the future would bring.

The Mausoleum has lost the top of its triumphal arch but the side columns remain.

In the late 1970s, the American cultural geographer J.B. Jackson wrote a thought-provoking essay called “The Necessity for Ruins.” He argued that ruins provide the incentive for restoration, and in words with strong religious connotations wrote that “the old order has to die before there can be a born-again landscape.”

Now a tourist attraction, the island prison Alcatraz fits Jackson’s definition of a born-again landscape. Or at least one that has been re-purposed.

Ruins appeal to us like haunted houses do, attracting us almost against our wills. Their empty spaces, once filled with doors or windows, are magnets for the imagination, and we fill those spaces with our own fantasies, with dreams of what was, or what might have been, or what one day may be.

The empty windows in this wall at the private garden La Torrecchia in southern Italy offer glimpses onto a verdant countryside in the process of becoming less verdant.

Romantic fantasies are part of the appeal. The Italian garden Ninfa, so redolent of the glories of bygone days, mixes the sour air of moldering walls with the powerfully sweet scent of lilacs and roses.

Ninfa has been called the most romantic garden in the world. The arched bridge is probably the most photographed spot in the whole garden, and the green tint in the water is part of its appeal.

But too much sweetness spoils the broth. To exert their full impact, ruins need a whiff of decay.

A temple at Siem Reap in Cambodia casts a spell which is particularly strong when approached in silence.

As Sir George Sitwell noted in his book, On the Making of Gardens, ruins where the patina of moss and age have been removed lose their appeal. The stillness of old Italian gardens, with their air of “neglect, desolation and solitude,” makes breathing almost too great an effort. We become unmoored, drifting in and out of time.

“Sleep and forgetfulness brood over the garden, and everywhere from sombre alley and moss-grown stair there rises a faint sweet fragrance of decay.”

An overgrown staircase, the Scala Santa, leads up the hillside at the Italian Villa Cetinale to the hermitage at the top.

Vegetation that is out of control adds to the appeal of a ruin, its growth suggesting that even in the most inhospitable circumstances, life will assert itself.

Rampant growth characterizes almost every ruin in Cambodia. The fig trees here threaten to swallow the roof of this temple.

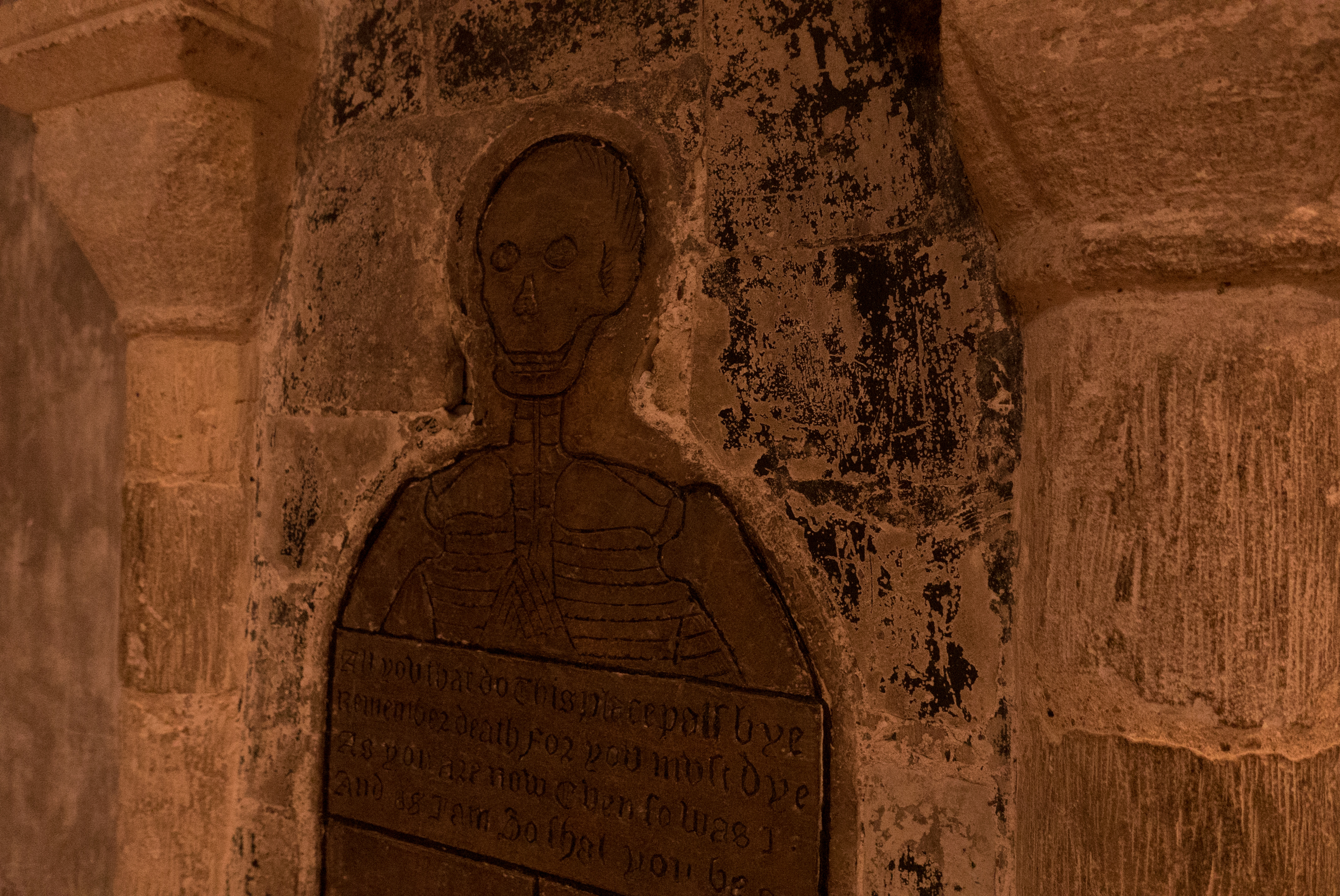

The combination of fecund nature and crumbling edifice conforms to the Christian doctrine that makes the death and decay of the individual a necessary prelude to resurrection. The skull beneath the skin and other allusive momemto mori are often seen in European churches and churchyards. Rarely are they as explicit, though, as the inscription that accompanies the skeleton below.

All you that do this place pass bye

Remember death for you must dye.

As you are now even so was I

And as I am so shall you be

Thomas Gooding here do staye

Wayting for God’s judgement daye.

This unforgettable tombstone is in the cathedral at Norwich, England.

Where, in the ruins of bodies and buildings, do we find today’s equivalent of Charles Hamilton’s water wheel? Where do we look for a future that promises recovery rather than ruin? Not for me in the contemplation of death or in the re-purposing that transformed Alcatraz from prison to tourist attraction. Not in the romantic dreams that speak to young girls’ hearts or in the political forces that have caused so much unnecessary suffering and pain. Hope seems to lie only in the natural world and its relentless tenacity. It alone seems capable of overcoming the follies we humans perpetrate — and let’s acknowledge it, we committed plenty of those in 2020.

Shelley’s poem Ozymandias speaks to the futility of aspiration. If worldly power can crumble, leaving only trunkless legs and a shattered visage, what is the point? The poppies that sprout from stone walls, the trees that split boulders, the weeds that emerge from cracks in the sidewalk, even the bare and boundless sand that stretches far away: they promise that the world will continue, with us or without.

Poppies are near indestructible flowers, a promise that life goes on, regardless of our stupidities.

I take heart from those poppies and from initials carved into tree trunks. Looking at the photo below, you may wonder why Andy felt the need to deface a tree in order to mark his presence. Was he the one who carved the hearts on the branch? Who knows, and who cares? His name, along with those hearts and the scrawls that were difficult to read when I saw them a decade ago, will be indecipherable soon, if they aren’t already. The tree will grow around them, obliterating the past in favour of its future health.

Andy’s name will slowly disappear from this tree trunk in West Australia.

I ask myself if anything good will come from this ruin of a year. Perhaps we will become kinder to one another. Perhaps more of us will realize that to take care of ourselves, we must also take care of others. Perhaps we won’t. But I hope that we will.

An uplifting essay for a strange year. I was glad to be reminded of the beauty of past times and what thoughts they evoke as ruins.

I’ve been surprised by the number of people who have told me (not by commenting here, though) how much they like ruins. I thought I was an outlier! Happy New year, Lisa.

Thank you Pat for this thoughtful story. It moved me. I love how evocative ruins can be when seen in silence. By the way, I recall the first time Tom and I visited the magnificent ruins of Fountains Abbey and came away knowing what the word “reredorter” means.

Susan d’Aquino

It’s always a pleasure to know that people read and respond positively to what I’ve written. Fountains Abbey is magnificent! And thanks to you, I now know the meaning of reredorter…. plus how it connects linguistically to reredos. Happy New Year!

Ha! I think snapped the exact same pictures in Cambodia!

I love both your gardening and your photos!

I bet most of us tourists took the same photos — and why not? The sights and sites are so evocative. Glad you like my gardening and photos, thank you!