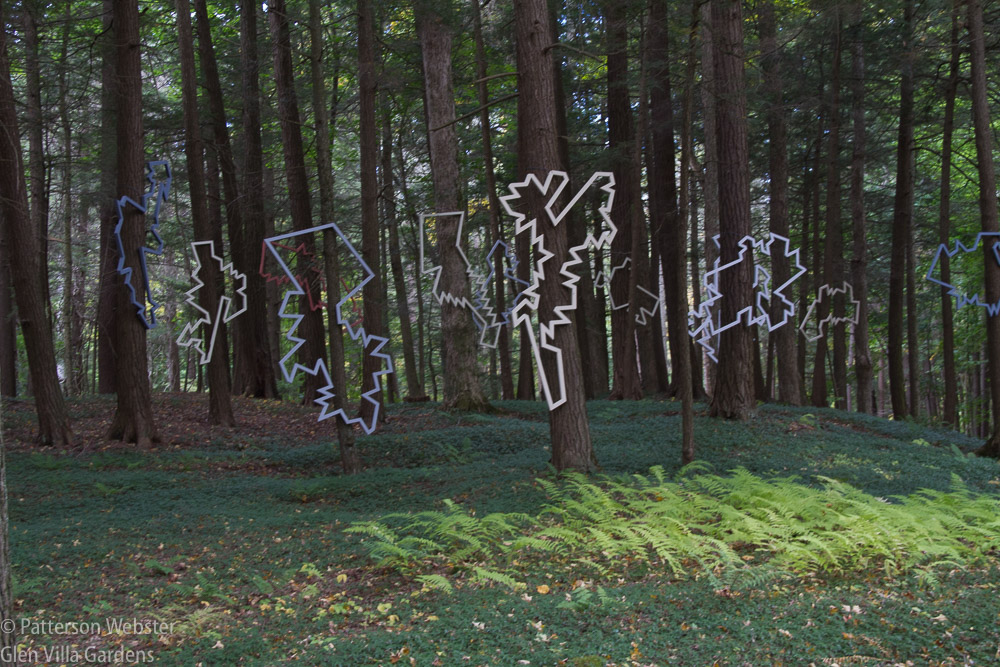

Just over a year ago I began work on a project in the woods at Glen Villa, my garden in Quebec. I was inspired by an exhibition I saw at The Mount, Edith Wharton’s home in western Massachusetts. One piece in particular caught my eye, a collection of oddly shaped pieces of wood that contrasted in an interesting way with the straight vertical tree trunks around them.

Cognito, a sculptural installation by William Carlson

I knew almost immediately that I wanted to do something similar and it took me only a few minutes of thought to decide where I wanted to do it. Home again at Glen Villa, I photographed the forested site I had chosen and considered the sort of shapes I would make.

Does something man-made catch your eye?

But while poking around in the woods, I came across the remains of a low stone wall.

Finding that wall changed my mind.

My husband grew up at Glen Villa and knows the woods well. When I mentioned the stone wall, he told me that a sugarhouse used to be there. He remembered working occasionally with Orin Gardner, the farmer who worked for his father, helping to collect the sap and watching Orin boil it to make maple syrup.

I knew Orin when he was an older man — and a very fine man he was. So I knew straight away that my project in the forest would not consist of randomly shaped pieces of wood. Somehow maple leaves would be involved, and maybe other things connected with making maple syrup as well. But most clearly I knew that the project would honour Orin and his connection to the land.

I started collecting the rusty bits and pieces of the former syrup-making operation that I found on site. There were many of them — cans, pipes and bits and pieces I couldn’t identify.

This lid once covered a bucket that sap dripped into. Now the maple tree has grown around it, making it a permanent feature of the forest.

Searching in the leaf litter, I found more.

This rusty tin can was meant to be filled with the maple syrup that Orin made.

But the luckiest find was the base of the pan where sap was boiled to transform it from a watery liquid to a thick sweet syrup. I wasn’t sure how I would use this remnant from the past, but I knew it would feature prominently.

This twisted piece of metal now sits at working height above ground, supported on a purpose-built metal frame.

What intrigued me more than the remnants, though, was the site itself. It was magical. My friend John Hay said he could see what had gone on there as clearly as if it were happening in front of his eyes. The challenge, we agreed, was to enhance the magic without destroying it. Something more was needed — the moss-covered stones, the only sign of what once had been there, were easy to miss. And I didn’t want people to do that. I wanted them to experience the magic as John and I had, as my sister Nancie had, as everyone who stopped and noticed seemed to do.

That meant adding something. But what? John suggested putting tree trunks where the corners of the building had been. I tried that, but they didn’t ‘read’ well, simply disappearing into the forest around them.

Three of the four corner posts are in place but it is next to impossible to see that anything has been added.

What instead? A side wall? A door?

No, a roof. A tin roof like every sugarhouse has, but rusted and falling apart. The triangular peak would stand out from the tree trunks around it, sunlight would reflect on the metal and the tin might even produce a sound when the wind blew, something hollow and ghostly.

It’s easier to see at least one of the corner posts in this photo. But seeing them against the roof line, I knew they had to be taken down.

It took two attempts to get the angle of the roof right — suspending twisted pieces of rusty metal from unevenly placed tree branches takes some fiddling. Once the roof was in place, the role of the pan where sap was boiled became obvious. It would sit squarely at working height beneath the roof, the focal point of Orin’s Sugarcamp. It would become the reason for the roof being there, a table that people would approach almost reverentially.

A photo from October this year shows the roof and elevated boiling pan.

Last fall we started to clean up the surrounding woods, chipping dead branches and removing the occasional tree. As the space became clearer, so did my ideas. I sketched maple leaves, deliberately distorting the shape to suggest how a real leaf changes shape in the fall. I gave the sketches to a local metal worker and he cut several different sizes out of tin. As real leaves were falling, we added the tin ones, suspending them in mid-air as if they too were floating to earth.

Over the winter as the leaves weathered I watched them move in the wind. Or not move. We used wire to hang the leaves and it was too stiff. The leaves didn’t turn and twist as I wanted. The shape was wrong as well and the way they were hanging didn’t look natural.

This leaf may look ok in the photo but it didn’t look right up close.

So this fall, when I ordered more leaves, I used the shape of a real maple leaf, undistorted. I ordered three different sizes of leaves, some two feet across, some 3 feet, some 4, in a heavier gauge of tin. For safety, I decided to hang the leaves from rods inserted into the trunks of trees instead of hanging them from rotting branches. And instead of wire I decided to use cable that would allow the leaves to move more freely.

For the last few weeks, off and on, we’ve been hanging the leaves. This job is tricky and time-consuming. Each metal rod needs to be drilled, and there are 60 of them. Each leaf is drilled, and in a slightly different place so that each one hangs differently.

My grandson David, age 10, drilled the holes in the rods. Thank you, David!

The actual installation is trickier still. Walking back and forth in the woods, looking from every direction, I decide where each leaf is to go, where on the tree it should hang, and at which angle. Jacques Gosselin and Ken Kelso, the ‘we-can-do-anything’ men who make my work at Glen Villa a joy, drill a hole in the trunk and hammer the rod into place. They thread the wire cable through the hole in the rod and the hole in the leaf, then crimp the wire to hold the leaf in place. And this is the trickiest part. The cable between the rod and the leaf needs to be as long as possible so that the leaves look natural, twisting and turning as they fall. So Jacques and Ken do all this 12-15 feet above ground, standing in the bucket of a tractor that is extended as high as it will go.

Standing unprotected in the bucket of a tractor 15 feet above the ground is not a practice I recommend. But Jacques and Ken are fearless.

So far we’ve hung about thirty leaves and the site is beginning to look the way I imagined.

About half the leaves are in place. Depending on the weather, we may finish hanging the rest this month. Or the job may have to wait until the snow melts.

Building Orin’s Sugarcamp has not been a rush job. At each step of the way I’ve stopped — for a day, a week, a month or two — to let a new element settle into place. I’m waiting now for one final piece. At the doorway of the sugarhouse, or where the entry would have been, I’m installing a slab of granite 10 feet long and 8 inches wide. It will be almost flat on the ground, but like a real threshold, you will have to step up onto it to enter. On the upward face of the stone will be a quotation that suggests how I feel about the site, the people connected to it and the work they did there.

It’s an unusual quotation that I came across at Little Sparta, Ian Hamilton Finlay’s garden in Scotland, And while I don’t mean to be coy, I’m keeping the quotation to myself until the stone is safely in place.

Once the granite has been installed and all the tin leaves are hanging, I may decide to add something more — another section or two of the tin roof, perhaps. Or I may decide to take something away. I have to wait and see. But I’m certain that the site will work its magic, clearly pointing the way.

I remember so well visiting this part of the woods, Pat, and what you are creating is, without doubt, magical, reflecting as it does Orin’s ghostly presence. Add to this the fact that by taking your time to complete the installation you are reflecting the slow drip, drip of the sap as it collects in the buckets ready to be boiled into delicious maple syrup, a process that cannot be hurried. The leisurely pace gives you time to refine the installation into its final form, much as the sap is refined into its end product. I am looking forward to reading the mysterious quotation on the upward-facing stone slab… You must be thoroughly enjoying tinkering with this particular work until you achieve the result you seek. And I wouldn’t guarantee that you won’t go on tinkering with it in the years to come. Thoroughly satisfying, both in its concept and its execution.

Thank you for your comment, Gill. I had never made a connection between the slow drip of sap and my slow pace in developing the project. I may indeed tinker with it in the future — how often are we content to leave well enough alone?

I like this and once again you highlight history with your talent for art!

Thanks, Robert. I’m doing what I can to make history visible on the land.

Bravo Pat! Très inspirant!

Nicole Benoit

Merci, Nicole!.

Oh, I really like this project! I’m glad you have the help you need to install it.

I am incredibly fortunate, Kathy. Jacques, Ken and I were out this afternoon hanging leaves. Probably the last day we can work in the woods, unless winter holds off.

Oh, Pat- I love this post and can’t wait to learn what Hamilton Little Sparta quote you used.

How fortunate you are to have such a crew, grandson included!

I’m delighted to hear from you, Dennee. I don’t want to lose touch.

I spent about five hours today, at just barely above freezing temperatures, hanging more maple leaves. This may be the last day… the snow that fell last week has mostly melted but it will come again, far too soon.

Pat Webster

Visual Artist, Writer, Speaker

glenvillaartgarden.com http://www.facebook.com/GlenVillaGardens

I love the floating metal leaves. How great that your grandchild was involved in making this happen.

He loved being involved. It’s too bad he was only visiting!