“No matter how panoramic its scope, a view of surrounding countryside becomes a genuine garden picture only when it has been framed.”

– Penelope Hobhouse

Recently I came across this statement from the English garden writer and designer Penelope Hobhouse. I read it quickly, nodded in agreement, then paused and read it again. Did I agree? Does a view have to be framed in order to create a ‘garden picture’? And what is a ‘garden picture’ anyway? a photograph of the garden or the picturesque scene itself? The more I considered the statement, the more I questioned it. What does ‘genuine’ mean in this context — that the ‘garden picture’, however defined, is unstaged? that it shows an accurate version of what we would see in person? that a framed view is somehow more authentic than an unframed one?

Framing a view is a common device in garden design. So perhaps Mrs. Hobhouse was simply suggesting that a framed view highlights the control that garden designers exercise over nature, or over what we see and don’t see. But I wonder if there isn’t more to it than that.

Certainly a frame controls, by directing our view. Sometimes the frame narrows what we see to a single feature.

A door in a brick wall at The Grove, the garden of the late David Hicks, frames the view of a stone pyramid beyond.

Sometimes it directs our feet on a particular path.

A pair of trees frame a view of nothing in particular at Naumkeag, in Massachusetts. The mown path directs your eye along the path; your feet follow.

Sometimes it establishes a symmetry that nature may lack.

In this Massachusetts garden, two urns, a hedged path and arching trees impose balance on the asymmetrical hills in the distance.

Often the frame is created by urns, shrubs or trees deliberately placed.

At Little Sparta, trees frame a view of one of Ian Hamilton Finlay’s inscribed poles.

Sometimes trees growing on their own accomplish the same thing.

This view of Lake Massawippi is framed by the trees. The chairs in the foreground give a sense of scale and add a human touch.

But whatever device is used, and whether it is used deliberately or accidentally, a frame directs the viewer’s eyes towards one thing rather than another. And by doing this, it imbues the focal point with significance.

I don’t mean to suggest that this is a bad thing. Far from it. I have framed many views at Glen Villa, both in the garden proper and in the woods that surround us.

Columns and a decorative wooden railing frame the view of the entry to the China Terrace, the imaginary re-creation of the resort hotel that once stood on the property. They direct the eye towards what lies beyond and focus it on a central feature, the dining room table.

By framing a view of the dining room table, I’ve made it the most important feature on the China Terrace. Only after looking at it do people notice other elements.

Window frames on the front and back walls of the China Terrace do the same thing. Whether the viewer is on the China Terrace looking out …

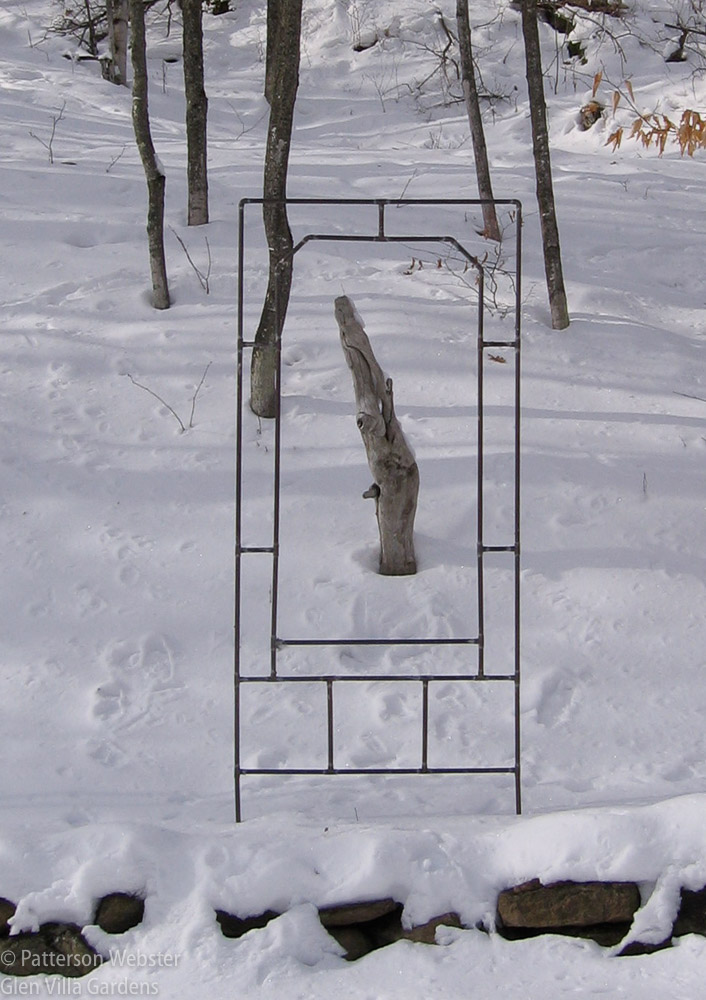

I placed this interestingly shaped piece of wood in the snow to give a focal point for the wintertime view.

or on the outside looking in, a framed view says there is something there to see.

There is no focal point to the view framed by this ‘window.’ Rather, the window frame draws your attention. Perhaps it even makes you wonder what lies beyond.

Framing works well in photographs. A picture of our house becomes more interesting when it is framed by the horizontal and vertical lines of the gateway that separates the Lower Garden from the wilder sections of the garden that follow.

An architectural element frames the view of our house.

Almost anything can frame a view. Most often, the frame is symmetrical, like the pair of Chinese lions, or fu dogs, that have been protecting our house since the early 1970s.

The pair of Chinese lions or fu dogs have moved with us from one house to another. Now they frame the view of the neon sign on the Log Terrace.

But asymmetrical framing can work, too. The branches of a juniper bush that was slowly dying became a framing device when I removed the last bits of foliage and planted an interesting evergreen within the bare framework.

The bare branches of a juniper frame a poodle pine in the Gravel Garden. Three Yucca filamentosa add exclamation marks.

We are accustomed to seeing framed views and, because of our experience, we generally accept the idea that an unframed view lacks focus. A framed view has a point to make. The frame itself emphasizes this. It tells you that something inside the frame is worth looking at, worth paying attention to. Because without a doubt, when you frame a view you are telling people to look at it from a particular vantage point. You are also telling them more subtly to look at the view and think about it in a particular way.

The framed signs that lead a walker along a trail in the woods at Glen Villa are an example of this. Writing on these signs asks questions, and the empty circular space in the centre of the sign invites viewers to peer through at the view beyond.

A viewer peers through the clear glass at … ???

Most people will expect to see something special when they look through the opening — after all, that’s what experience leads us to believe. But in this case, the view shows nothing unusual.

The circle in the square is a Chinese symbol for the universe.

Which is precisely the point I wanted to make. By showing a view of the forest scene that contains nothing special, I hope that people will come to realize that every part of the forest is special, not only framed views that are ‘picturesque.’

Other picture frames at Glen Villa form part of an installation in the Upper Field. Abenaki Walking traces a history of the original inhabitants of Quebec’s Eastern Townships from creation to the present day. Some scenes from this history are framed, others are not. The framing device I used is not a pair of trees or shrubs or urns, but rather actual picture frames, large enough to contain all of a particular scene.

The first picture frame outlines a distant view. Framed, yet so far away that they almost disappear, are some stick figures and a stone mound that, on closer examination, turns out to be a turtle with a colourful pole rising up on its back.

A picture frame directs peoples’ eyes towards a distant view. The label at the bottom of the frame says Abenaki I, 4500 B.C. The label as well as the actual frame tell people how I want them to see, and understand, the scene.

A second frame shows a closer view of a different part of the Abenaki’s story.

Framed here are tree limbs inverted to suggest figures walking. The ‘walkers’ are tangled in barbed wire. Behind them is a rail fence, the sort of fence built by European settlers in the mid 1800s.

Viewers determine what part of this scene is framed by choosing where to stand. They can, for instance, include or omit in their framed view the wooden post that, in the photo above, is outside the frame. They may study the inverted branches, consider the implications of split rail fences and barbed wire as part of an installation titled Abenaki Walking, or they may glance at the scene and move on. They may or may not wonder what that post has to do with the rest of the scene. Do the white blotches mean something or are they merely decorative? And does their meaning change if they are inside or outside the picture frame?

The post is painted with the smallpox bacillus, the disease bought to North American by the European settlers.

Actual picture frames impose meanings that more standard garden framing devices do not. Trees and shrubs direct our view, picture frames transform those views into paintings. Obviously the scene we see through the picture frame at Glen Villa isn’t an actual painting, but the allusion remains. The connection is there in the back of our minds. And because we most often consider paintings to be things of value, framing the view in this way adds importance to what we see. The frame causes people to look at it and think about the scene in a particular way, a way they might otherwise not consider. It freezes the scene to a particular moment in time, as a painting does, and suggests that a static image tells the whole story.

Framing a view controls what is seen. The control can be aesthetic or it can be allusive, ambiguous, allegorical. In every case, though, a deliberately framed view imposes a designer’s point of view. It is up to the viewer to accept or reject that view.

Do you agree?

Pat, I do agree, and you’ve given a marvelous design lesson on framing here. I’ll be thinking about your framing techniques as I continue making my own garden and visiting others. Pam/Digging: http://www.penick.net/digging

What a compliment, Pam. Thank you.

I agree that there are frames all over the place whether we see them or not; we are looking through them as we focus on the scene.

I’ve spent the last few days at a friend’s house, talking about the design for her new garden. Framing views was definitely high on our minds. It was surprising to see how many naturally framed sight lines there were, even in a ill-defined space.

Great photos, and although that last spotted red post represents a tragedy, it’s beautiful.

Thank you, Cindy.

I added a big picture frame on an easel to my garden this year and am looking forward to seeing the plants behind the frame bloom. I think how a garden is ‘framed’ is vital, although sometimes we simply have to work with what we have so the ‘frame’ may be a bit lacking. My favorite view is of the lake through the trees.

I’d love to see the frame and flowers, Tammy. Can you send me a photo when they bloom? or even now?

The view right now is fairly unfabulous since a heat wave while I was traveling burned the clematis growing around the frame and the flowers behind it have yet to bloom. But I’ll post it on the blog this fall. 🙂

I look forward to seeing it.