How do you choose a name for a house and garden? What goes through your mind when you do?

History was the determining factor for my husband and me when we chose the name Glen Villa — it was the name of an old resort hotel that once stood on the property. It was also the name my father-in-law used for the property in the years he owned it. So although the previous owner had dropped the name, when we acquired the land in 1996, we chose the name in a flash.

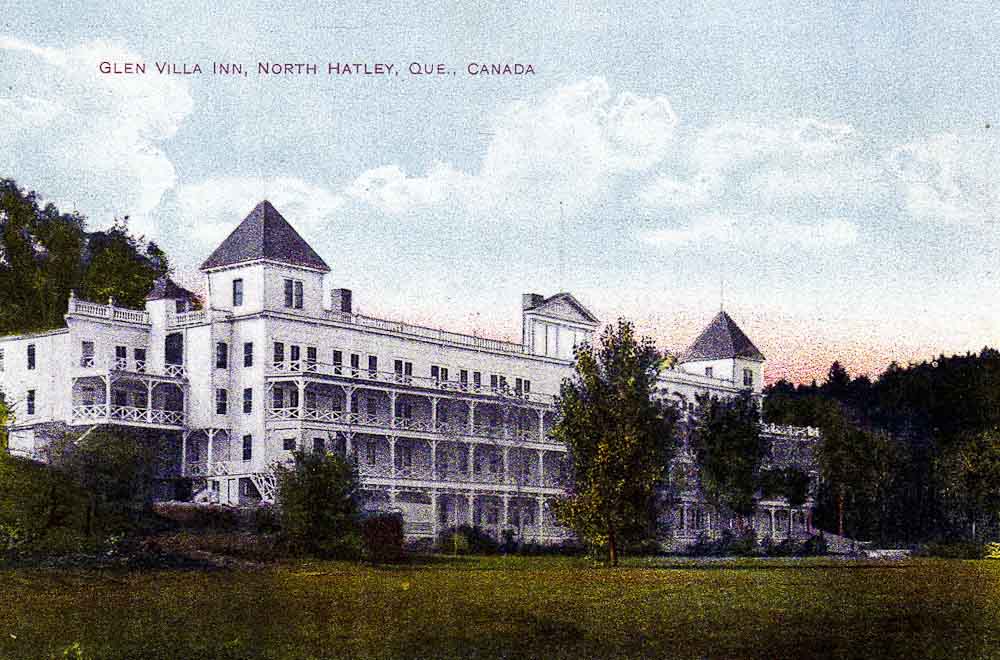

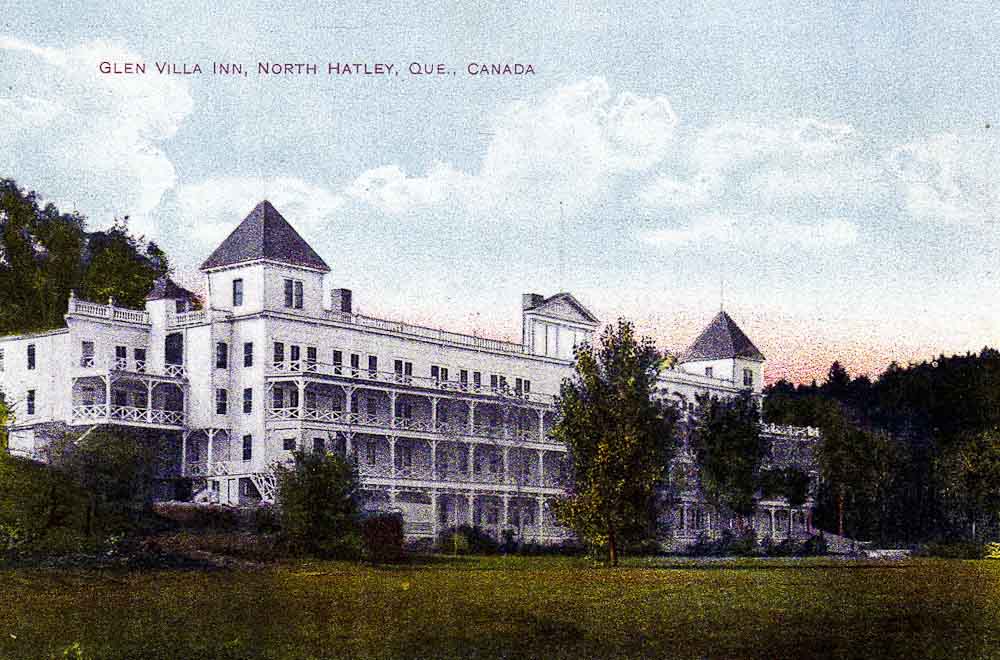

Glen Villa Inn was a resort in the old style. Built in 1902, it was a big, wooden building open only in the summer. The man who built it liked to say it had 365 rooms, one for every day of the year. I’m sure that was an exaggeration, but even so, it was an impressive edifice.

The owner, George Albert LeBaron, knew how to promote his property. He produced a brochure that sold the hotel’s qualities to the people of the day in a way that you have to admire, or at least have to laugh about. Glen Villa, he wrote, offered the perfect environment: “free from malaria and hay fever… void of mosquitoes and black flies…no fog, no mist.” Best of all, it was “sufficiently removed from large city centres and the excursion element to assure refined patronage.”

My father-in-law discovered a copy of this brochure many years ago and passed it on to me and my husband.

Those refined patrons got a great deal. Glen Villa cost $3 a day or $18 a week, including meals. It also had every facility a turn-of-the-century patron could wish for: swimming, canoeing, tennis, carriage rides through the woods, a bowling alley, billiard tables, a dance hall — and a nine-hole golf course, one of the earliest in the area.

In the 19th century, North Hatley attracted hundreds of summer visitors, from Maryland and Virginia in particular. Canada was a real draw for these southerners. They wanted to leave the heat and humidity of the south but they didn’t want to spend time with the Yankees who had just defeated them in the American Civil War.

So they came across the border from Yankeeland, to North Hatley. And they came in great numbers. According to the local newspaper, in July 1900 there were over 800 summer boarders, from most of the states in the Union, all of whom were “very gentlemanly and ladylike.”

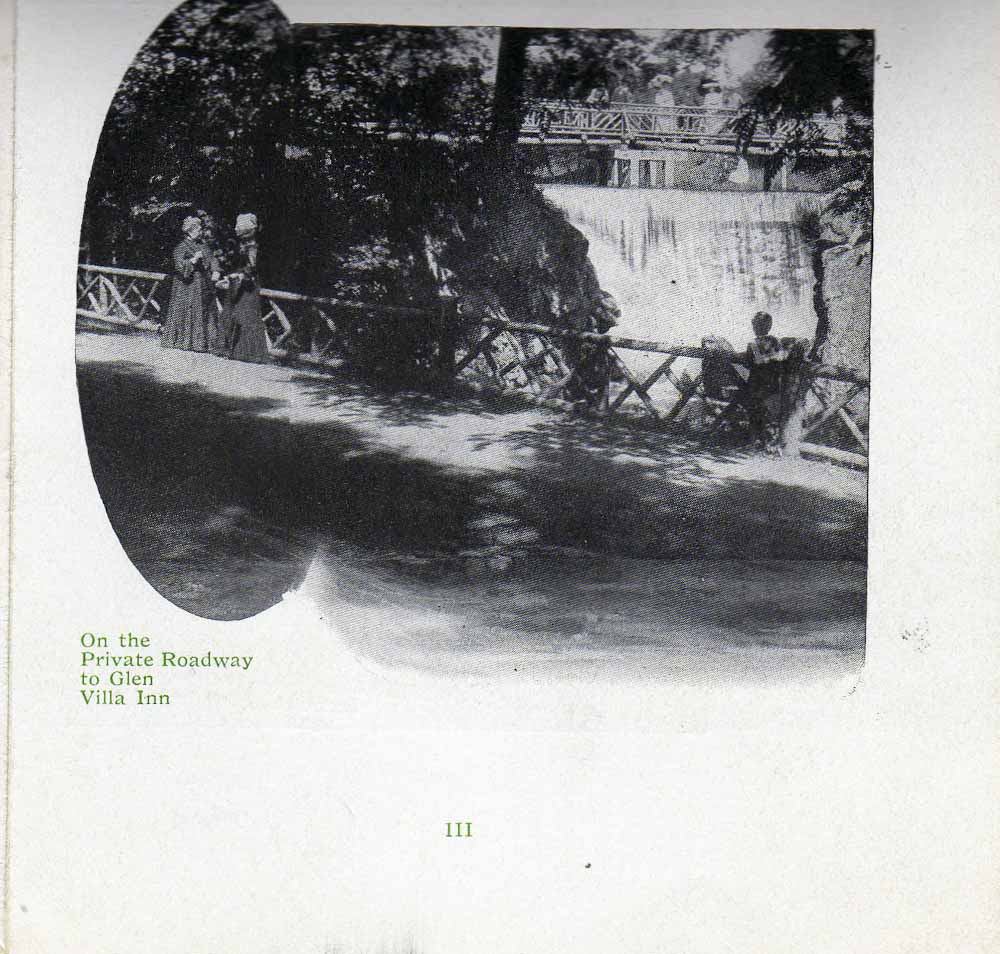

This photograph from the hotel brochure shows one refined patron sketching the waterfall at Glen Villa while two others are having a chat. Dressed in black, the ladies may well be Civil War widows from the south.

In his advertising Mr LeBaron focused on the convenient location. Guests could board a train at New York’s Central Station in the evening and arrive at North Hatley the following morning, without ever changing trains. A commonly told story, probably apocryphal, said that the southern ladies pulled down the blinds as soon as they boarded the train, to avoid even seeing the north as they passed through.

On arrival in North Hatley, Glen Villa’s private launch would take them the mile and a half across the lake. A short walk up the asphalt path and they would reach the hotel itself.

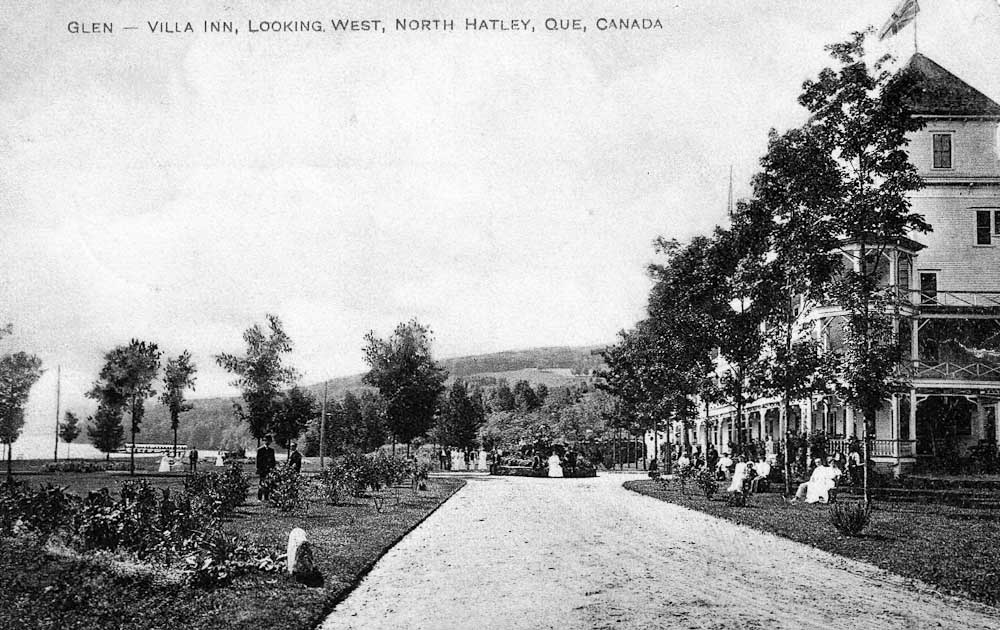

A side view of Glen Villa Inn. More refined patrons are lounging on the lawn and a young lady in white is sitting on the low stone wall that encloses the ‘yin/yang’ at today’s Glen Villa.

The hotel didn’t last long. In 1909, as it was about to open for its 8th season, the hotel caught fire and was destroyed overnight. This is what is left of Glen Villa now: a foundation wall covered with Virginia creeper and wild honeysuckle, held together by the vines even as they tear the stones apart.

Remnants of the foundation wall of Glen Villa Inn crumble a little more every year. Repairing them really means rebuilding, which we are not prepared to do.

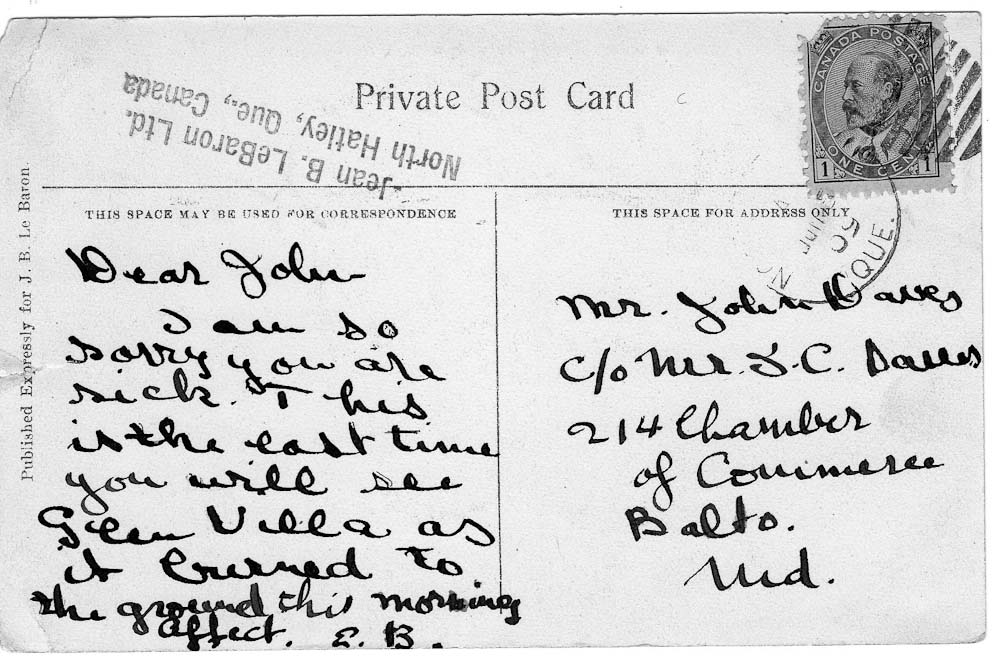

A postcard from the period mentions the destruction of the hotel succinctly and without emotion. “This is the last time you will see Glen Villa as it burned to the ground this morning.”

I haven’t successfully identified the sender, E. B., but as you can see, the recipient was a Mr John Daves from Baltimore, Maryland. Was John trying to forget the recent unhappiness caused by the Civil War (or the War Between the States, as I was taught to call it, growing up as I did in Virginia)? Or was he rejoicing in the results? He could have held either view: Maryland was a border state where sentiments were divided equally between the opposing sides.

The split in views might have caused problems for the American visitors who summered in North Hatley, since they came from both the north and the south. But it seems that politics were left behind. A general from the north lived in a cottage on one side of Glen Villa, a general from the south lived in a cottage on the other. Apparently they got along quite well.

Or so the story goes

I love all this history of the Hat and you probably know that there were two three others not as big that burned too, but not really documented. I think that boat that carried them to the Glen Villa is sunk in the bay just before you get to MacIntosh’s at Black Point. Richard Bradley and myself used to dive to it and I think we pulled off a wood cleat too.

Over the years there were three or four different steamboats on the lake. I know the name of three: the Pride of the Valley, the Massawippi and the Pocahontas. The Pocahontas operated during the days of Glen Villa Inn. I know about the boat off Black Point.but don’t know its name.

I will check with Richard but the Pocahontas does it!