On the weekend we installed the granite slab that marks the ‘front door’ of Orin’s Sugarcamp, my latest art installation at Glen Villa. (You can read about the project here.)

Doing this was tricky. It involved transporting an 800-pound slab of rock across a snowy field and a partially frozen stream on the back of an open wagon. That takes skill, particularly since the snow is very slippery right now. But Jacques Gosselin and Ken Kelso, the talented men who work for me at Glen Villa, managed the job with ease.

A small stream marks the boundary between the field and the woods beyond, where Orin’s Sugarcamp is located.

Orin’s Sugarcamp is a short distance into the woods, along a well-worn track. The tin maple leaves we hung several weeks ago to define the area are now partly covered with snow. Seeing them sway in the wind and hearing the bell-like sounds they make as they lightly touch one another transformed the job from a scary endeavour into a magical experience.

The area now covered primarily with spruce and hemlock was once a maple forest. In the 1950s and 1960s, Orin Gardener produced maple syrup here.

The wagon with the granite slab was hooked to a tractor which Jacques drove slowly across the field. He drove even more slowly across the stream, then carefully continued along the forest track, avoiding potholes and icy patches.

The slab is ten feet long. Even though the granite was well protected by boards and a wooden crate, I was nervous that it would slide out of the wagon and crack when it hit the ground. Thankfully that didn’t happen.

He and Ken attached chains from the crate to the tractor, then lifted the slab out of the wagon and lowered it into place.

Jacques and Ken are skilled workers who can operate almost any piece of equipment, even under difficult conditions.

The slab marks the threshold to a sugarhouse that used to exist, whose history the project honours. With snow covering the ground, it isn’t possible to position the slab precisely; that job will have to wait for spring, when the snow has melted.

The granite slab is a portal. Stepping onto it, symbolically you enter another time and place. The inscription underlines this movement from the everyday world into a place that resembles a shrine.

Come springtime, we’ll make some minor adjustments — lowering the central table where syrup was boiled, for one, and possibly adding some steps to lead up to the ‘front door’. But for now, with the granite doorstep more or less in place, the work on Orin’s Sugarcamp is finished.

Last week, though, before the granite slab was delivered, we added one more element to the area, something simple that I think adds to the apparent reality.

Compare the before photo…

This photo is from October when we first started hanging the tin maple leaves.

with the after. Can you spot the difference? And do you think the addition helps or distracts?

This photo is from the end of November, when we had only a light frosting of snow.

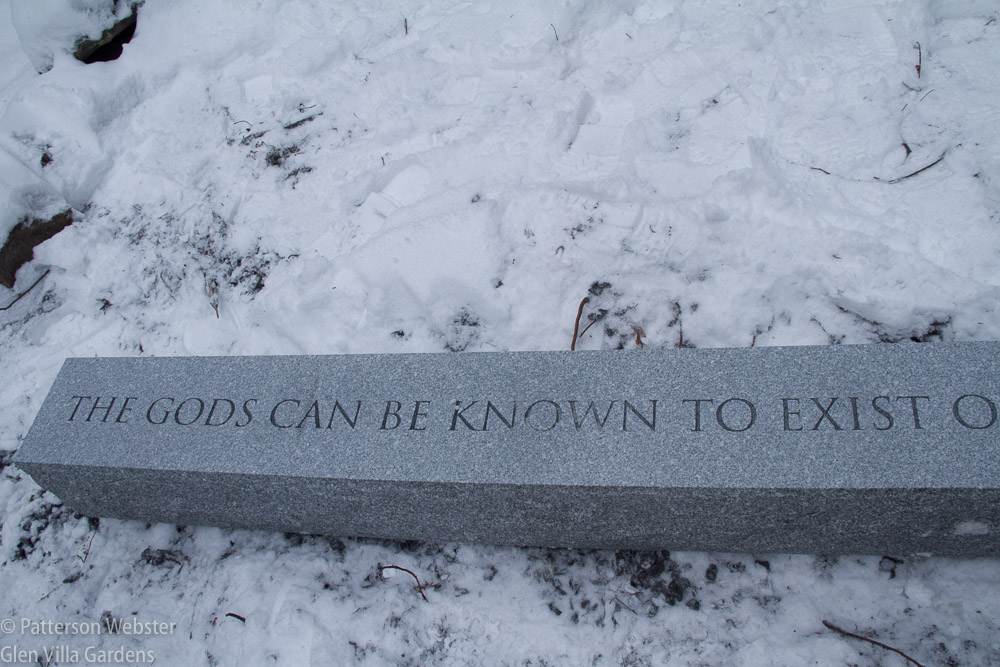

Finally, let me share with you the words I chose to be cut into the stone. They are a quotation from Chrysippus, a Greek Stoic philosopher who lived in the 3rd century BCE.

A single photo won’t show the whole quote, so here is the first part …

When I spotted this quotation at Little Sparta, Ian Hamilton Finlay’s garden near Edinburgh, I knew right away that I would use it at Orin’s Sugarcamp. It simply felt right.

and here’s the second. The work was done beautifully by Rock of Ages, Stanstead , Quebec.

The Gods can be known to exist on account of the existence of their altars.

At Little Sparta, the quotation appears inside the temple of Baucis and Philemon. This small building celebrates a story told in Ovid’s Metamorphosis about an elderly couple who offered shelter on a cold night to Zeus and Hermes, not knowing who they were. It’s a familiar idea, told again and again in fairytales and with Christian equivalents.

The Gods rewarded Baucis and Philemon by transforming their cottage into a magnificent temple. A few gold tiles on the roof show the beginning of the transformation. As for Baucis and Philemon, they were first made priests of the temple; when they died they were transformed into trees marking the entrance. That transformation is also shown as being in progress.

I was tempted to shorten the quotation but decided not to. While at first reading the words seemed redundant, the more I thought about them, the more they seemed to reflect the complexity of an idea. (I can’t judge the accuracy of the translation, nor do I know whose translation it is.) Chrysippus did not simply state that gods exist and that altars prove the fact, but rather that we are able to know about the existence of gods through the memorials we make to them.

No god is being worshipped at Orin’s Sugarcamp, not even the god of sweetness known as maple syrup. What I am celebrating, and recognizing through the quotation, is the work that was done in this place and the people who did it. A simple stone wall was all that remained of a sugarhouse where syrup was produced over many years, and always in a traditional way. Horses pulled wagons around the sugarbush, collecting sap from buckets nailed to the trees. The sap was boiled, canned and labelled, then sent out to be enjoyed by people I knew and people I didn’t.

Orin’s sugarcamp, as it looks now.

Orin’s Sugarcamp is my attempt to bring a bit of that past into the present, so that others may carry the memory of what happened there into the future. It’s my tribute. My altar, if you will.