Slowly the wall that used to hold up the old Glen Villa Inn is beginning to look like a wall again.

As exciting as the re-building are the treasures we discovered when the wall came down. We found glass bottles of all sorts, clear and coloured, broken and unbroken.

Some of the bits of glass were plain, some more decorative.

A clear glass jar with nicely interlocking circles saying Ripans tabules came from Ripans Chemical Company, New York. Thanks to an on-line search and information from The Toadstool Millionaires, I now know that the bottle we unearthed once held a patent medicine said to “benefit dyspepsia and illnesses from a disordered stomach.” The company’s name ‘Ripans’ was made up from the first letters of the product’s ingredients: rhubarb, ipecac, peppermint, aloes, nux vomica, and soda. Contemporary advertisements praised the virtues of these ‘tabules,’ a word made-up by the manufacturer, claiming “No matter what’s the matter, one will do you good. They banish pain, induce sleep, prolong life.” Apparently there was also a chocolate coated version.

I didn’t need to look on-line to find information about the bottle below — its name made its purpose clear, even if its shape hadn’t done that already.

I find to my surprise that an on-line market exists for these bottles, both of which date from the late 19th or early 20th century. You can buy a Ripans bottle on ebay for U.S. $24.99 and any number of ink bottles of different shapes and colours for even less.

As well as the clear and coloured bottles, our treasure trove included the base of a broken but still attractive candlestick, part of an oil lamp, a punch cup and the top of a salt shaker. The richly coloured blue bottle made by Wm R. Warner & Co. was yet another medicine bottle, and while I haven’t found information about what type of medicine it was, I imagine it was another miracle ‘tabule’ designed to cure all ills, induce sleep and prolong life.

Is there significance in the fact that the two medicine bottles we discovered were made in the U.S. and all the broken china we discovered was made in England? The hunter green design on the cache of broken plates and saucers seems even now an appropriate choice for a country inn, even though the pattern name Recherché does not. According to marks on the bottom, the ‘Imperial Semi China’ was made by Dunn Bennett & Co. Burslem England sometime between 1891 and 1907. Since Glen Villa Inn was built in 1902 and burned down in 1909, the china must clearly have been used in the hotel.

The blue fragment below, pattern name ‘Woodford,’ may have been a soap dish. It was made by Dalehall Pottery, a company that seems to have existed for one year only, 1892. Did Mr. LeBaron, Glen Villa’s entrepreneurial builder, get a good deal on the dishes, or was a still-colonial Canada the china’s dumping ground? And why did the company go out of business? One of partners in the enterprise was Edward Alfred Wedgwood so perhaps Dalehall was absorbed by the more prominent and longer established company. Or perhaps it simply went under.

Along with broken glass and pottery, we uncovered metal bits and pieces — the metal rims around barrels, old nails and pieces too bent to identify. For me, these treasures are signs of the past that tell stories or raise questions. I like Mr. Warner’s blue bottle and Underwood’s ink jar; together they remind me of the Skipp’s Peacock Blue ink that once was all the rage. But perhaps my favourite treasure is this bent and rusty horseshoe.

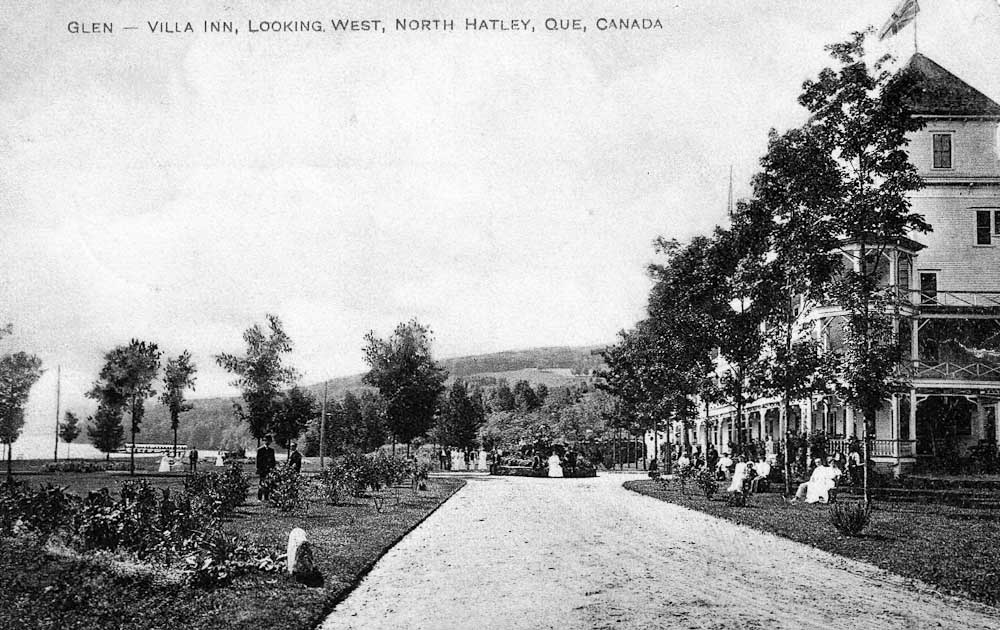

It makes me think of the horse-drawn carriages that brought guests to the front door of the Glen Villa Inn, how the horses must have slowly circled the low stone wall where the lady in white is sitting in the postcard below. Thinking of those horses makes me think of how much more slowly life moved then, how different the problems were from those we face today. Or, after a slightly longer thought, to wonder if our problems were similar after all.

A side view of Glen Villa Inn. Notice the lady in white sitting on the low stone wall.

Now that the area around the wall has been cleared, I know that we won’t find any more treasures. Nor do I know what I’ll do with the ones we’ve found. Perhaps, like the broken pieces of china I discovered shortly after we moved into Glen Villa in 1996, they will sit in the basement for years until an idea occurs to me.

China shards form this mosaic welcome mat at the entry to the China Terrace, my installation that recalls the old hotel.

Or maybe not. Maybe I’ll rebury this newest treasure trove in the re-built wall, leaving it for someone else to discover years from now.

How delightful to uncover the past in this way! I always enjoy the stories that objects carry with them, whether they’re functional objects or not.

So do I, Lisa. And most objects do seem to carry a story.

Probably lot’s more to find as I would assume everything just got buried on the property as to hauling off the rubble to a dump, yes no!

We keep discovering bits and pieces in strange places, but nothing more on the site of the hotel wall.

Your beautifully posed photos already do the broken glass great honour….

What a nice comment, John. Thank you.

This is wonderful! You should definitely do something with the bits and pieces.

Any ideas about what to do with them?

Our previous home had a spot where we think garbage was burned by the earliest residents. It was in the chicken yard and the chickens were always digging things up: bottles similar to yours, marbles, and even two sleigh bells. At our current 19th century home, there is one bed where I keep digging up metal. Horseshoes, nails, hinges, etc. I think it is near where a barn used to be. It does make you think about the previous occupants and what their lives were like. It was slower, but also quieter, I think. No cars, tractors, chain saws, blowers–not to mention all the things that make noise inside the house.

You are SO right about the noise level. When I go into the city I stay overnight with my son and his family. They live on a fairly quiet street but I am so much more aware of the noise and the street lights. In the country it is quiet and dark… just as I like it!

Such great stuff! I don’t know if you remember, but at one point I wrote about finding 1930s era whiskey pint bottles hidden between the studs when we renovated the kitchen.

I don’t remember that post, Jason, but it’s definitely a find worth remembering. (or drinking?) We renovated a cabin that used to belong to Frank Scott, a poet and law professor at McGill University, and found his university reserved parking spot sign, also between the studs. You have to wonder how such things ended up where they did.